Blake & Shakespeare

Texte intégral

1On 12 September 1800 Blake wrote to his close friend, the sculptor John Flaxman, to thank him for his help in introducing him to a new patron at a time that he was in need of work:

I send you a few lines which I hope you will Excuse. And As the time is now arrived when Men shall again converse in Heaven & walk with Angels[,] I know you will be pleased with the Intention & hope you will forgive the Poetry. (Blake to John Flaxman, September 12, 1800)

2What follows is a verse autobiography of Blake’s early life. For a poet whom few would normally associate with Shakespeare, it is revealing:

To My Dearest Friend John Flaxman

Now my lot in the Heavens is this; Milton lovd me in childhood &

shewd me his face.

Ezra came with Isaiah the Prophet, but Shakespeare in riper years gave

me his hand

Paracelsus & Behmen appeard to me. terrors appeard in the Heavens

above

And in Hell beneath & a mighty & awful change threatened the

Earth

The American War began All its dark horrors passed before my face

Across the Atlantic to France. Then the French Revolution commencd

in thick clouds (Blake to John Flaxman, September 12, 1800)

3As Blake was born in 1757 and the “The American War began” in 1776, these lines of verse autobiography incorporated in his letter to Flaxman make clear that when “Shakespeare in riper years gave [Blake] his hand,” he was possibly still a boy or more likely in his teens; in 1776, he would have been age 18 and in the fourth year of his apprenticeship to James Basire. Following Milton, the Old Testament prophets Ezra and Isaiah, and the Renaissance mystics, Paracelsus and Jacob Boehme, Shakespeare marked not only a mature influence, but also a comparatively secular one. But in what ways did Blake respond to and appropriate Shakespeare?

i.

4Blake’s first collection of poems, Poetical Sketches, was printed privately in 1783. The volume, as the “Advertisement” informs us, was “the production of untutored youth, commenced in his twelfth, and occasionally resumed by the author till his twentieth year.” It is divided roughly into two parts; the first composed mostly of lyric poems and the second of dramatic and prose fragments. Here we find what we might expect.

5Eight songs at a stroke displace the still fashionable late eighteenth-century Augustan poetic diction and replace it with simplicity of expression characteristic of the lyric poetry of Ben Jonson and especially the music of Shakespearean song. The last of these songs, “Mad Song,” could have been taken down from Poor Tom on the heath in King Lear. Here indeed the hand of Shakespeare is palpable.

Like a fiend in a cloud

With howling woe,

After night I do croud,

And with night will go;

I turn my back to the east,

From whence comforts have increas’d;

For light doth seize my brain

With frantic pain. (“Mad Song”)

6King Edward the Third is the longest of three dramatic fragments. Composed of six scenes and altogether nearly 1,000 lines of dramatic blank verse, it is a substantial piece of juvenilia. The cast list should be noted as including both Edward III and his queen, Queen Philippa.

7In the second year of his apprenticeship, Blake’s master, James Basire, accepted a commission from the antiquary Richard Gough to prepare drawings for what would later be published as the Sepulchral Monuments of Great Britain. Basire duly instructed Blake to make drawings for engraving, in particular of the kings and queens buried in the central chapel of Edward the Confessor in Westminster Abbey. These included the tomb of Edward III and his queen, Queen Philippa. One can imagine the hours Blake spent in the Abbey and how he would have thought about and tried to learn all that he could about his subject, clearly exploring the life of Edward for his play in an attempt to fill a gap in the canon of Shakespeare’s history cycle.

8In 1776 Blake was at work in making the drawings, as he recalled to Flaxman, when the “awful change threatened the Earth” that was the onset of the American war of independence. The opening scene of King Edward the Third is “The Coast of France, King Edward and Nobles, The Army.” Edward addresses his armies:

When confusion rages, when the field is in flame,

When the cries of blood tear horror from heav’n,

And yelling death runs up and down the ranks,

Let Liberty, the charter’d right of Englishmen,

Won by our fathers in many a glorious field,

Enerve my soldiers; let Liberty,

Blaze in each countenance, and fire the battle. (King Edward the Third)

9This began Edward’s ill-starred invasion of France. Bloody slaughter followed, then retreat, the Black Death, and the perpetual conflict that became the Hundred Years War. We remember the famous remark of Queen Elizabeth “I comparing herself to Richard II” in 1601 at the time of the Essex rebellion: ‘I am Richard II. know ye not that?” If Blake’s King Edward the Third (which is only six scenes) was written at the time of the revolt of the American colonies, which seems likely, he may be suggesting a similar historical analogy. In this case, of Edward at the outset of his invasion of France, standing for King George III at the outset of what will become the debacle of the American War of Independence.

10The manuscript of An Island in the Moon (1784–87), as Martha England and David Worrall have suggested, may have been written in the form of a burletta for performance at the Haymarket Theatre– where just such a mixture of dialogue and song was required if the patents of Drury Lane and Covent Garden were not to be breached. If there is a Shakespearean influence, as I believe there is, one need look no further than the marvelous good fun enacted in Act V, scene i, of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, when the group of “mechanicals” enact the story of “Pyramus and Thisbe.”

11Blake’s other early manuscript, Tiriel (c. 1787), as often noted, is reminiscent of Shakespeare’s King Lear; the blind Tiriel who confronts and curses his sons and daughters clearly conflating Shakespeare’s characters of Gloucester and Lear. Such lines as those when Tiriel “raisd up his right hand to the heavens” and curses his sons, are clearly suggestive of Shakespear’s protagonist:

Serpents not sons [,] wreathing around the bones of Tiriel

Ye worms of death feasting upon your aged parents flesh (Tiriel)

12As a young man learning his craft these examples of Shakespeare’s influence or appropriation are what we might expect of Blake.

ii.

13By 1788 Blake had worked out the revolutionary method of “Illuminated Printing” that would enable him to combine his poetry and designs together and to publish them himself. One of the first volumes that he published using his new method was the Songs of Innocence in 1789. By 1789 Blake had absorbed Shakespeare; indeed, I suggest that Shakespearean drama had become second nature to him. But it would no longer manifest itself in obvious dramatic terms, such as we have seen in King Edward the Third or in his early manuscripts.

14What Blake has learned from Shakespeare is the use of dramatic personae and point of view. Like Shakespeare, Blake steps back from the first person singular traditionally associated with the English lyric. Instead, and again like Shakespeare, Blake becomes not only the creator, but director, even stage manager. Blake’s Songs are dramatic vignettes. The characters who appear in each of his Songs are his cast and the accompanying designs his sets.

15“The Little Black Boy” of Songs of Innocence is typical. It begins as though the theatre lights have just been dimmed, and the character of the little black boy has stepped out onto the stage alone, to introduce himself.

My mother bore me in the southern wild,

And I am black, but O! my soul is white;

White as an angel is the English child:

But I am black as if bereav’d of light.

My mother taught me underneath a tree

And sitting down before the heat of day,

She took me on her lap and kissed me,

And pointing to the east began to say. (“The Little Black Boy”)

16Notice how quietly the drama begins to unfold, just like a Russian doll, a second character is introduced, then a third–for example, the voice of Christ the Shepherd recalled by the mother–and so on.

17Like so many of the Songs, one could explore the poem much further. For example, where in the “southern wild” could the mother of the little black boy have heard the comforting words of Christ of the New Testament that she has imparted so successfully to her son, that he has never forgotten, and that psychologically have been his mainstay as a little black boy presumably in London? Were the words of Christ heard by the mother from a missionary? How was it that the mother and her son became separated? The questions mount, the drama continues to unfold.

18When we turn to the Songs of Experience, first published separately in 1793 and combined with the Songs of Innocence the following year, there are appropriations from Shakespearean of far different pitch and tenor. Blake’s “London” must be a result of Blake reading, reciting, and ruminating upon one after another of Shakespeare’s soliloquys.

I wander thro’ each charter’d street

Near where the charter’d Thames does flow

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.

In every cry of every Man,

In every Infants cry of fear,

In every voice: in every ban,

The mind-forg’d manacles I hear

How the Chimney-sweepers cry

Every blackning Church appals,

And the hapless Soldiers sigh

Runs in blood down Palace walls

But most thro’ midnight streets I hear

How the youthful Harlots curse

Blasts the new-born Infants tear

And blights with plagues the Marriage hearse. (“London”)

19Here is another example of a very different kind that I believe demonstrates how deeply and totally Blake absorbed Shakespeare, so deeply that in this example it may be said to well up from within and manifest itself in the prosody, in the very beat and cadence of the lyric.

20Blake drafted the Songs of Experience from 1791 through the Spring of 1793, exactly the time that disillusionment with the French Revolution became widespread in Britain, particularly after reports reached London of what were called the Paris Massacres in August and September 1792. The overthrow of the monarchy inexorably led to the execution of Louis XVI in Paris on 21 January 1793, followed in February by France’s declaration of war against Britain and Holland. During this same period Blake drafted both “London” and “The Tyger.”

Tyger, Tyger, burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

In what distant deeps or skies,

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand, dare seize the fire?

And what shoulder, & what art,

Could twist the sinews of thy heart?

And when thy heart began to beat,

What dread hand? & what dread feet?

What the hammer? what the chain,

In what furnace was thy brain?

What the anvil? what dread grasp,

Dare its deadly terrors clasp?

When the stars threw down their spears

And water’d heaven with their tears:

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the Lamb make thee?

Tyger Tyger burning bright,

In the forests of the night:

What immortal hand or eye,

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry? (“The Tyger”)

21Are we meant to hear resonating through the cadence of Blake’s lyric the following lines from Act IV, scene i, of Shakespeare’s Macbeth? The witches have hailed Macbeth at the beginning of the play predicting that he will become king. With his having committed the regicide, and having taken the throne of Scotland by force, they now prophecy his downfall:

Double, double, toile and trouble;

Fire burne, and Cauldron bubble.

Fillet of a Fenny Snake

In the cauldron boyle and bake:

Eye of the Newt, and Toe of Frogge,

Wooll of Bat, and Tongue of Dogge:

Adders Forke, and Blinde-wormes Sting,

Lizards legge, and Howlets wing:

Likke a Hell-broth, boyle and bubble.

Double, double, toyle and trouble,

Fire burne, and Cauldron bubble. (Macbeth, Act IV, scene i)

iii.

22Finally, I would like to look at Blake as an illustrator of Shakespeare. Not examples of his commercial engraving work in illustration of Shakespeare’s text, but, by far more tellingly, at an example that he selected to illustrate for his own purposes. Illustration seems an inadequate expression for what in fact is the transformation of Shakespeare’s word into image. Again from Macbeth, I refer to the Large Colour Print of 1795 entitled Pity. [Fig. 1]

23In 1794, Blake turned his attention from the production of his illuminated books to painting. He began by producing two drawings and then a colour-printed drawing in illustration of the lines from Macbeth’s speech in Act I, Scene vii, in which Macbeth contemplates the murder of Duncan:

And Pitty, like a naked New-borne-Babe,

Striding the blast, or Heavens Cherubin, hors’d

Upon the sightless Curriors of the Ayre,

Shall blow the horrid deed in every eye,

That teares shall drowne the winde. (Macbeth, Act I, Scene vii)

24The Large Colour Print of 1795, a monotype, is remarkable for its visual articulation of the passage, significantly, without compromising its import. The “sightless Curriers of the Ayre” are at full stretch as “Pity like a New-born-Babe” twists its body to reach up to the outstretched arms of “Heavens Cherubin.”

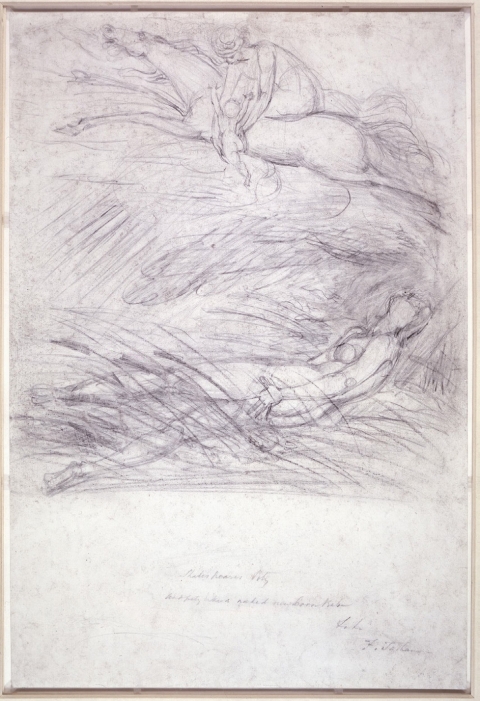

25We can follow the evolution of the design, and thereby his exploration of the passage, in two preliminary pencil drawings and an experimental colour-printed drawing [Fig. 2]. In the first drawing, the face of the forlorn figure of humanity is hidden, but expressed by her outstretched hand with fingers wrenched in pain. The first drawing is in an upright or portrait format and significantly, in terms of the evolution of the design, spatially presented on two planes–the figure of the woman reclining on the ground in the foreground, with the figures above her set back.

Fig. 2. William Blake, preliminary drawing for Pity, portrait format, c. 1794. BMPD accession number 1874,1212.148.

26In the second drawing [Fig. 3], the format has been changed to landscape, with both groups now brought forward into the foreground composed into a single, highly concentrated image. The head of the woman is now in profile, thrown back, expressionless, as though in a trance, her arm by her side and hand out of view. It is the second drawing that Blake chose to copy on to copper, confirming his decision, for the moment, to set aside the illuminated book and to explore this image as a painter. But the significance of his decision was to do so as a printmaker.

Fig. 3. William Blake, preliminary drawing for Pity, landscape format, c. 1794, BMPD accession number 1894,0612.12.

27In preparing the trial colour print of Pity to etch in relief, Blake used a quill pen or fine brush, and the same stop-out varnish used in preparing his plates of the illuminated books for etching, drawing only the bare and simplest outline of the contours of the second drawing on to the copper plate, unconcerned that it would be reversed in printing. When the plate had been etched and cleaned, Blake prepared it for colour printing. Let us examine the experimental colour print of the design [Fig. 4]. Try to imagine it without the watercolour washes and the lines in pen and ink that have been used to define the figures. These were added later, as I will explain. Onto the copper plate from which he printed this image, Blake applied only broad areas of glue and gum-based colour pigment, first along the top, leaving an even larger area below it for the horse, rider and child to be introduced and defined later. He left another sweeping area running from left to right free of colour, in which he would later define the reclining figure. However, across this space Blake then drew a series of strokes– leaning, as in the first drawing, from right to left, to simulate reeds or rushes swept by the wind in the wake of the “sightless Curriers of the Ayre” who are “striding the blast.” In other words, he chose to apply colour to little more than one-third of the surface area, leaving the rest of the copper plate untouched. This is how it was printed. Only when the impression had dried, sealing the glue-based pigments, were pen and ink used to define the images, followed by thin watercolour glazes applied with great delicacy and subtlety to introduce flesh tone and atmosphere.

Fig. 4. William Blake, experimental colour print for Pity, c. 1794, BMPD accession number 1874,1212.380.

28In the months that followed Blake realized that he could simplify his method even further. This was the breakthrough. On the scale of landscape paintings (c. 440 x 580 mm), Blake abandoned the etched or engraved matrix with which he could reproduce exactly the same image every time it was printed. Instead, following the simplest of un-etched outlines he applied his mix of gum- and animal-glue-based pigments onto broad areas of the copper plate or pasteboard, leaving other areas entirely untouched. Placing the plate on the bed of the copper-plate rolling press and laying his sheet over it, Blake then printed an impression, using only the slightest pressure as plate and paper passed between the rollers. But enough pressure that when the sheet was pulled from the plate the vacuum that resulted as the sheet was lifted away from the plate created the highly reticulated and mottled surfaces that characterize the Large Colour Prints, that under magnification look like the surface of the moon. Simply but wonderfully, once set, the blotches and blurs of colour pigment that had been printed-and that Frederick Tatham who knew Blake in his last years would later describe as having an “accidental look” about them-Blake transformed, first by defining areas with pen and India ink to create facial and bodily expression and then with glazes of transparent water colour wash to modulate colour and tone.

29This was the first attempt at creating a revolutionary graphic medium, the monotype. Before Blake in the seventeenth century only Benedetto Castiglione had made a handful of experiments that remained virtually unknown. After Blake the monotype would not be tried again until those of Edgar Degas’s in the 1870s, followed by Picasso and countless artist-printmakers in the twentieth century.

30For Blake, this was an even more radical and revolutionary development than the invention of his method of “Illuminated Printing,” and for the subject of his first attempt at creating the monotype Blake had turned to Shakespeare. In doing so, he had selected one of the most complex and searching of Shakespeare’s metaphors, one at the very heart of perhaps his darkest tragedy. As we have seen, step by step, Blake explored its depths, appropriated and then transformed Shakespeare’s word, bringing to light for all to see and ponder its significance in visual terms. But just how remarkable was Blake’s image? Set against the two most famous examples by his contemporaries we will be in a better position to judge.

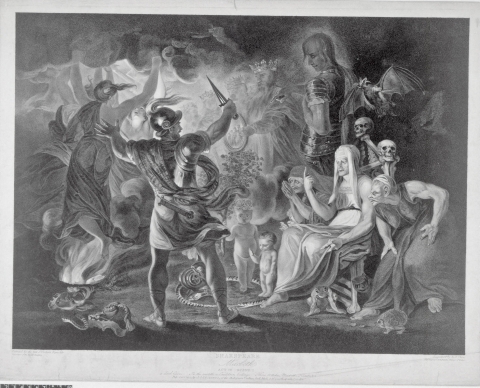

31The two paintings are by Sir Joshua Reynolds, Macbeth and the Witches, Act IV, Scene i, now in Petworth House, and Henry Fuseli’s, Macbeth, painted in 1793, now in the Folger Shakespeare Gallery. What is significant is that both paintings were simultaneously put on display and deliberately juxtaposed in 1793 in Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery, just at the moment when Blake first experimented in colour printing and within possibly months of choosing the image from Macbeth that he would illustrate.

32First, here is an engraving after Reynolds’s painting [Fig. 5]: As contemporary critics quickly noted and criticized, Reynolds has gathered together on the same canvas a huge number of images. Here is an engraving after Fuseli’s painting [Fig. 6]. As also noted by critics at the time, in contrast Fuseli has concentrated his image into a single moment. The response at the time makes clear that the two paintings represented two very different notions of artistic genius. Fuseli chooses to depict and isolate a single expressive moment, in contrast with Reynolds, who conflates a succession of dramatic events and figures—an armoured head, a bloody child, a crowned child carrying a tree, a witches dance, &c.—each with its own significance within the scene of the play. We might be tempted to say that in this regard Blake is clearly of the school of Fuseli and, like Fuseli, has concentrated his colour print upon a single expressive moment. I would disagree and say that in fact Blake goes much further. Indeed, if one can draw an analogy, what we are seeing in Blake’s choice of subject and his handling of Shakespeare’s imagery is an exploration of the “deep structure,” the underlying syntax at the heart of Shakespeare’s art [Fig. 1].

Fig. 5. Sir Joshua Reynolds, engraving published 1 December 1802 after his painting Macbeth and the Witches, in illustration of Macbeth Act IV, Scene i, for the Shakespeare Gallery of Alderman Boydell commissioned in November 1786, BMPD accession number 1977,U.773AN146919001.

Fig. 6. Henry Fuseli, engraving after his painting in illustration of The Witches Appear to Macbeth and Banquo, in illustration of Macbeth Act IV, Scene i, also for Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery, BMPD accession number 1863,0509.55.

33What distinguishes Blake’s Large Colour Print known as Pity from the paintings in illustration of Macbeth by both Reynolds and Fuseli is that both are still paintings in illustration of the text. Blake’s image probes deep beneath the surface of the play, beneath any single character, scene, or act. It may be said, either to transcend illustration altogether, or, to bring to the surface the very heart and substance of what Shakepeare’s darkest tragedy is in essence all about and consumed by.

Table des illustrations

|

|

|---|---|

| Titre | Fig. 1. William Blake, Pity, Large Colour Print c. 1795, Tate Britain. |

| URL | http://preo.ube.fr/interfaces/docannexe/image/319/img-1.jpg |

| Fichier | image/jpeg, 408k |

|

|

| Titre | Fig. 2. William Blake, preliminary drawing for Pity, portrait format, c. 1794. BMPD accession number 1874,1212.148. |

| URL | http://preo.ube.fr/interfaces/docannexe/image/319/img-2.jpg |

| Fichier | image/jpeg, 403k |

|

|

| Titre | Fig. 3. William Blake, preliminary drawing for Pity, landscape format, c. 1794, BMPD accession number 1894,0612.12. |

| URL | http://preo.ube.fr/interfaces/docannexe/image/319/img-3.jpg |

| Fichier | image/jpeg, 510k |

|

|

| Titre | Fig. 4. William Blake, experimental colour print for Pity, c. 1794, BMPD accession number 1874,1212.380. |

| URL | http://preo.ube.fr/interfaces/docannexe/image/319/img-4.jpg |

| Fichier | image/jpeg, 1,4M |

|

|

| Titre | Fig. 5. Sir Joshua Reynolds, engraving published 1 December 1802 after his painting Macbeth and the Witches, in illustration of Macbeth Act IV, Scene i, for the Shakespeare Gallery of Alderman Boydell commissioned in November 1786, BMPD accession number 1977,U.773AN146919001. |

| URL | http://preo.ube.fr/interfaces/docannexe/image/319/img-5.jpg |

| Fichier | image/jpeg, 1,2M |

|

|

| Titre | Fig. 6. Henry Fuseli, engraving after his painting in illustration of The Witches Appear to Macbeth and Banquo, in illustration of Macbeth Act IV, Scene i, also for Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery, BMPD accession number 1863,0509.55. |

| URL | http://preo.ube.fr/interfaces/docannexe/image/319/img-6.jpg |

| Fichier | image/jpeg, 1,9M |

Pour citer cet article

Référence papier

Michael Phillips, « Blake & Shakespeare », Interfaces, 38 | 2017, 157-172.

Référence électronique

Michael Phillips, « Blake & Shakespeare », Interfaces [En ligne], 38 | 2017, mis en ligne le 13 juin 2018, consulté le 29 janvier 2026. URL : http://preo.ube.fr/interfaces/index.php?id=319

Haut de page