- 1 Georgia Russell is a Scottish artist, born in 1974, who has lived in France since the beginning of (...)

1The work of the contemporary Scottish artist, Georgia Russell, uses books as a medium, transforming them into sculptures.1 In this digital age, these book sculptures represent a reflection on the book in its paper form, one shared by an increasingly large number of artists, such as Brian Dettmer, Doug Beube or Guy Laramée, to mention just some of the best known. While it has existed at least since the 18th century, the art of sculpting books seems to have become more frequently developed recently, as a reaction to the advent of the all-digital era (Dettmer 10). If the works of these artists have a tendency to highlight a certain cultural erosion they paradoxically do so by cutting books.

2This article deals with the substantial role of book sculptures in the work of Georgia Russell, where some words from a book are systematically highlighted by the cut of a scalpel. I will also see how the artist appropriates these words, transforming them into an almost organic materiality, her sculptures in paper becoming metabolic figures where the temporality of the artistic gesture gives way to the immediacy of reading. I will examine the relation between the title and its material substance and the way it is highlighted and reactivated. I will question the function of Georgia Russell’s book sculptures, the modes of sensory access which are brought together, the zones of contact, or not, between literature and sculpture, and how a new, expanded, materiality is created. The aim of this article is to examine sensory patterns and ways of reading which are instituted by the relation between the text and the texture of these book sculptures.

- 2 The subsequent works by Georgia Russell mentioned in this article can be viewed on the England&Co. (...)

3Russell began to sculpt books when she first arrived in France. She found the book that she transformed into a sculpture for the first time at a stall on the banks of the Seine in Paris, while she was looking for a paper medium to make a chandelier for a video she was working on, dealing with notions of time and light. The work in question, Mémoire, subsequently “took on forms she would never have previously imagined” (Pilven 13-16)2.

4One can see through this story that the book’s title obviously influenced its transformation into a brainlike form. The title always plays an undeniable role in the relation between the reader and the text since it is the first thing the reader sees. It is a paratextual element which acts as an intermediary between the work and the reader. As with the preface, or the chapter headings and contents, it has an essential place in the “peritext” as defined by Gérard Genette in Palimpsestes. La littérature au second degré. It is the result of the encounter between the wording, in this case the words of the title, and the supposed expectations of the public or, as Charles Grivel explains, it is:

“This gesture by which the book is opened: the fictional content is now set, the reading perspective designated, the reply is promised. From the moment the title is read, ignorance, and the need for its reabsorption, are called for simultaneously. The activity of reading, this desire to know, represented from the outset as a lack of knowledge and the possibility to discover, is launched.” (Grivel 173)

5In the absence of any precise knowledge about the author, it is often on the strength of the title that one will choose to read, or not, a novel. It represents a “set of potential readings” (Grivel 173), a catalyst of mental images, a trigger of the imagination. Russell preserves this function of the book title and chooses the titles of the novels she works with according to their evocative value. The presence of the title in her works points to and displays the appeal of this evocative function of the word. Besides, she prefers short titles (e.g. Paroles, by Jacques Prévert). This attachment to short titles leads to her creating visual short-cuts relating to the dream-based approach of surrealism or psychoanalysis. Her starting point is a title reflecting universally shared notions (Le Bleu du ciel) or one which is just as evocative (Lolita). The artist also chooses titles which are emblematic of the literary influence of the work (e.g. A Room of One's Own; The Female Eunuch), or of a particular struggle or universal sentiment (e.g. L'amour; L'amour fou; Le Désir). In this respect the title is meant to represent the major concerns of humanity, with the artist questioning the history and temporality of existence (e.g. Années 2009).

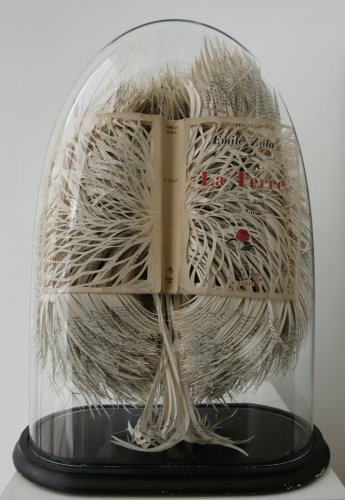

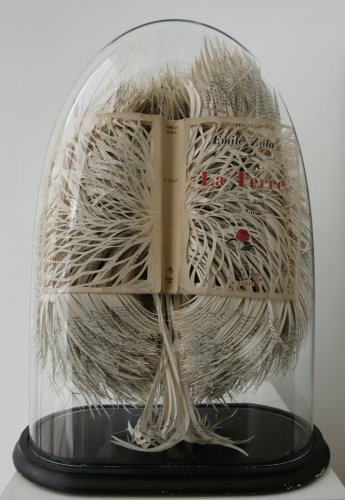

Fig. 1. Georgia Russell, La Terre, 2007, By courtesy of the artist.

© Georgia Russell

- 3 Breton, J.-A., Martin, H.-J. and Toulet J., « Livre », in Universalis.fr.

6One can presume that it is not the content of Zola’s La Terre which counts for the artist, but the significance of the two words making up the title which easily relates to the tree-like form of this book sculpture (fig. 1). The common denominator of all her works is the cutting out of the medium with a scalpel, a “spark” incision, or “pen-flame” as the critic Anne Malherbe so nicely puts it; the equivalent of her pictorial touch, since for her, cutting amounts to drawing (Malherbe 6). The temporality of her artistic gesture is similar to that of a painter, with whom she compares the regularity and rhythm of her touch. This act, combining gesture and rhythm, time and space, becomes fundamental to the work of the artist. One must emphasize here that by cutting books out her aim is to give them a new dimension rather than to destroy them. The composition of the book cover and its typography are also associated with the propensity of the title. By associating visual and textural notions, Russell re-injects into the title a visual dimension missing from the original book cover, which, while not directly referred to, is developed by her art. The artist in fact builds on the powerful evocative nature of the title, carefully conceived beforehand by authors and their publishers: it becomes part of this externalization of the book which semioticians have noted as being corollary to the gradual disappearance of illustrations in books, often replaced by the cover illustration (Breton, Martin, Toulet n.p).3

Fig. 2. Georgia Russell, Les Cahiers Obscurs, 2009, By courtesy of the artist.

© Georgia Russell

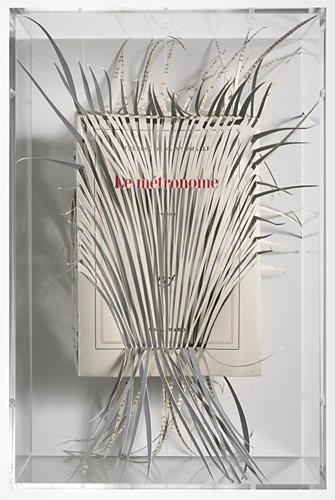

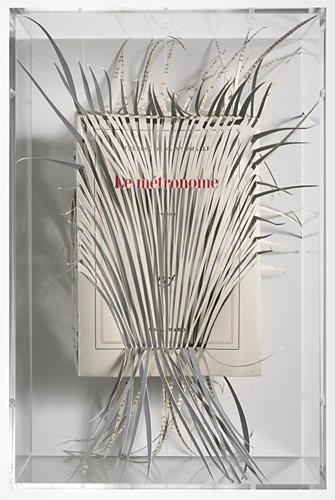

Fig. 3. Georgia Russell, Le Métronome, 2008, By courtesy of the artist.

© Georgia Russell

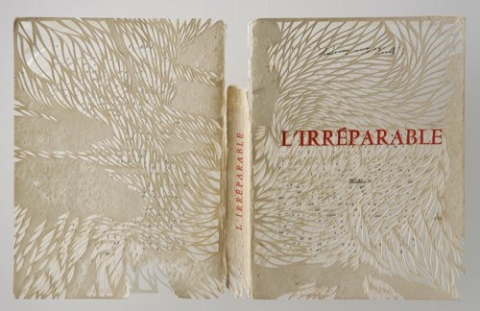

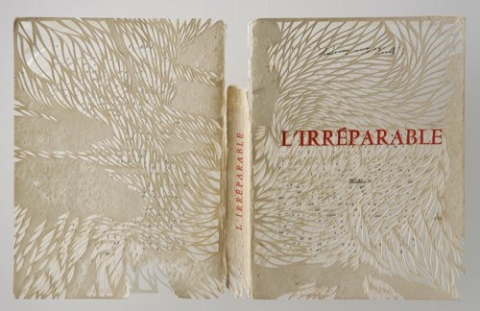

Fig. 4. Georgia Russell, L’Irréparable, 2009, By courtesy of the artist.

© Georgia Russell

7The perfect symmetry of the binding of Mariage parfait (The perfect marriage) provides another example of this formal amplification of the title. The declared aim of the artist is to use the title as a starting point to convert the book into something else than a book, thus proceeding to liberate its initial content and give it a totem-like shape. Russell revealed indeed in an interview that:

Cutting out is a sort of freedom of expression. When you cut something out, you free it. [...] I started cutting up books some twelve years ago. Little by little I started doing collages and then cutting out, and when I did the cut-outs, I saw there was something destructive which I found interesting in all that. In my opinion it wasn’t negative destruction but it freed a sculptural form of the book. For me they are like masks or totemic figures and I’m happy they’ve found a very human side. (Hourdequin n.p.)

8The artist's approach is somewhat reminiscent of Tom Phillips's Humument which begins with a book, and ends with a book, through the total restructuring of the original work and an attention to the book title. In 1965 Phillips found W.H. Mallock's 1892 novel A Human Document in a bookstore and turned it into a life-long work. The original title of Mallock's work, A Human Document, by the coincidence of a simple cut-out, became a portmanteau word, A Humument, a title which has been kept throughout its various editions. Since, Phillips has reworked the pages of the book like a palimpsest, using the gutters vertically formed between the words of the original text to better underline some words and turn them into poems. By superimposing illustration and text by means of collages emanating from the very pages of the book, and by creating flat areas of paint delimited like illuminations, Phillips made the silhouettes of two protagonists stand out. Throughout the various editions, a love story has unfolded between Irma, the heroine of Maddock's work, and Toge, a character created by Phillips from the words "Together" and "Altogether" found in the book. He has "deconstructed" and recomposed his book endlessly, in a contemporary palimpsest transformed into numerous works: paintings, watercolours and digital works encompassing ballet, opera and musical compositions (Craig-Martin, Davey, 198-203).

9Unlike Phillips, Russell’s book sculptures do not rewrite the narrative contained in the books she chooses to work on, but there is a similarity between these artists who both create contemporary palimpsests from found books they cut out, while paying a particular attention to book titles. There is above all in the work of both artists something typical of the transversal work of visual artists who use the book as a medium: they bring artists and authors together, whatever their era and medium, in order to produce a new work which has nothing to do with the first one but respectfully gives the original book another, free and poetic form.

10Besides, the linguistic and cultural notions of Russell’s works invoke the meaning of words, but also the diversity of languages in her attachment to dictionaries. Many are the book artists, including the best known mentioned in the introduction, like Brian Dettmer or Guy Laramée, who use these dense works as raw material for producing works in a complex volume form. Apart from dictionaries, it can also be almanacs, directories, encyclopaedias or paper atlases, works that no-one in this digital age wants anymore because of their bulky volume, and this free, accessible material is exactly what is sought by the artists. Sculpting paper is in fact more difficult than working the wood from which it comes; this artistic itinerary is one fraught with pitfalls and hazards, requiring raw materials which are still plentiful, accessible and cheap.

11In this respect Russell’s approach differs from those of her fellow artists, since she sculpts the book purely with the help of a scalpel, without the use of machines, thus limiting her possibilities to work on thick volumes. It is also perhaps why she often only retains the covers of the works that she uses. Hence, when the artist chooses to sculpt a dictionary rather than the cover page of a work, it is to “liberate” the words included in this book while never losing sight of its initial function which is that of a reference book. This approach is in contrast therefore to some other artists, who alter the function of the book by transforming them for example, into landscapes as in the case of Guy Laramée’s encyclopaedias turned into mountain ranges; or by reifying them in the form of objects other than books. A contrario, the dictionaries that she chooses retain the trace of their original function: the covers or the edges of the work, where the titles are still visible, constitute the principal axis from which words issue forth like flying sparks, taking on a literally tangible form.

- 4 Personal interview by the author with Georgia Russell, 9 January 2014.

12In these works, which have been anthropomorphized into masks, the initial volume of the book is less important than the human dimension it assumes. Placing them occasionally under glass bell-jars might constrict the freedom the artist seeks to impart to her works, but this process of enclosure emphasises the preservation of the paper book, this form of shared knowledge increasingly threatened by its digital counterpart. The artist reveals that the purpose of putting her works beneath glass bells is in fact, paradoxically, less a question of keeping the spectators at a distance from a precious work, than of enabling them to be at one with a work which is liberated and humanised, since they can see their own reflection appearing mirror-like on the recreated work.4 There again, the concern for her public is in this shared knowledge the book represents, in the evocations of the title which she seeks to exchange with the spectators, through the vision that they will also have of themselves, beyond the glass partition protecting her work.

13One talks perhaps too often of resorting to the image to counteract the incommunicability of language. One has for example spoken for a long time about the “book of images” which medieval stained-glass windows might have represented, without really questioning the iconographic complexity which rendered this medium comprehensible only to scholars of the time (Brisac, Grodecki, 24). Images without words are not necessarily meaningful and words without images either. We see here that conversely, by fantasising about the power of languages and words, Georgia Russell orientates our vision of her sculptures by keeping the book’s original titles, thus including the spectator in her mental approach process. The incommunicability of art, especially abstract art, means that many artists share this reliance on language where the title appears to complete their work, but also through recourse to words. Calligraphy and graffiti are two forms which also function in the same way by associating the textual and the visual to share an idea, whatever the prohibitions. In the case of Russell’s works, the artist’s imagination could never have been shared to the same extent with the spectator had she removed the titles of the works.

14The text-visual association is not exclusive to contemporary art but is reinforced in all abstract works, where the spectator is unable to focus her/his attention on the motif or a commonly shared iconographic system. According to the art sociologist, Nathalie Heinich, discourse has even become intrinsic to contemporary art, in the sense that it could no longer be understood without resorting to it (Heinich). The association of the textual and visual with Russell is certainly an example of this need for mediation by means of the word, but it should be noted that her tour de force lies in the fact that her work, still retaining the titles without which her individual works would become standardised, could dispense with any discourse. She uses only the very few words of each book title and obliterates the books’ original text by lacerating the pages beyond recognition, sometimes even applying on them an additional pastel wash. Through this association between two distinct semiotic systems, the artist transforms a familiar mostly textual medium into a visual metaphor. She enables the spectator to share her own imagination, her own interpretation of the original textual work, in an immediacy due to the concise title phrase that a complete reading of the books chosen would never have allowed. They form in this way a new dynamic of reading which engages the spectator by using collective representations where the boundaries with the elitist world of contemporary art can disappear, whether or not the viewer has read the original book.