Introduction

The 13th instalment of the Audit of Political Engagement released by the Hansard Society in 2016 opened with the following words: “Parliament knows it has a reputational problem with the public, which is why it is so important to understand the public’s attitudes, to reach out, and through action to turn cynicism (whether legitimate or not) into healthy engagement” (Fox et al. 2016: 5). Further down, it concluded: “E-petitions is the single most important route to engage the public that Parliament currently has at its disposal, apart from direct contact with a representative” (28).

And indeed, subsequent audits confirmed both the reputational problem mentioned above and the popularity of the e-petition platform introduced in the UK in 2011 and remodelled in 2015. The last instalment of the audit, published in 2019, showed that while core indicators of political engagement such as certainty to vote or interest in politics remained stable, “feelings of powerlessness and disengagement were intensifying”, with a record 47% of respondents stating their belief that they had no influence at all on decision-making at the national level (Blackwell 2019: 6). Meanwhile, creating or signing e-petitions remained the most popular form of online political activity alongside watching online politically-related videos, with 28% of respondents having done so in the previous year (27). And indeed, for the 2017-19 session of Parliament, the e-petition website recorded over 16 million unique users (Watson 2020).

Such concern for citizen engagement is not unique to the UK as for instance, several OECD reports have pointed out the need to include citizens in decision-making to improve the legitimacy of political institutions, from the book entitled Focus on Citizens Public Engagement for Better Policy and Services released in 2009 to the latest version of its Guidelines for Citizen Participation Processes made available in 2022.

Encouraging petitions so as to boost public engagement is a strategy which has also been used in a variety of countries through history but also more recently at the European level, with the Maastricht Treaty in 1992 officially recognising the right to petition the European Parliament, building on previous legislation from the 1950s, on the following premises:

The right to petition parliaments allows citizens close contact with an elected representative or political institution and the possibility to participate indirectly in the democratic process and influence the political agenda. Like referenda and popular legislative initiatives, the right of petition is a crucial element of a participatory democracy (Atanassov 2015: 2).

Participatory democracy is “concerned with ensuring that citizens are afforded an opportunity to directly participate, or otherwise be involved in the decisions that affect their lives” (Keugten 2021). For Keane however (2009), petitions belong to a model of monitory democracy, which adds power-scrutinizing elements to traditional representative democracy. Dalton et al. (2003) place them within the paradigm of advocacy democracy, a process involving direct participation in policy-making with elites retaining final control over decisions. As for the e-petitions introduced since the launching of the pioneering Scottish parliamentary platform in 1999, they undoubtedly belong to the field of e-democracy or “the usage of internet to enhance the democratic process by encouraging online civic engagement, online citizen participation, online discussion, blogs etc.” (Holzer & Manoharan 2011: 412).

Given the novelty of e-petitions and the hopes placed on them to stimulate public engagement with political institutions, they were naturally the object of robust research. Alathur (2007) for instance produced a case study of petition usage in India and concluded that “e-petitions can empower citizens to engage effectively in efforts to fight for their […] rights”, a position broadly shared by Cotton (2011) or Wright (2016). As for Åström et al. (2014) in the Swedish context or Berg in Finland (2017), they argued that e-petitions could help overcome a feeling of helplessness from citizens regarding political decision-making. Beside engagement, other issues related to petitions were explored. Alexander (2009) for instance tried to find out the reasons why people signed petitions, Aragón et al. (2018) the role of social media campaigning in ensuring success, and Clark & Lomax the linguistic and semantic factors making petitions popular (2020).

In the UK and regarding parliamentary platforms more specifically, the Scottish Parliament has actively tracked the performance and effects of its system through internal reports and collaborations with academics. But there is limited self-assessment available for the Westminster platform, with only a few reports, such as the one released by Ruth in 2012 or the one produced by the petition Committee in 2016, both covering very narrow timeframes. Yet Dumas et al. (2017) together with Panagiotopoulos and Elliman (2012), suggested that governments could benefit from the information derived from these vehicles of popular expression, making a broader case in favour of academic research focusing on such data and processes.

And indeed, such research on British initiatives does exist. Asher et al. (2017, 2019) for example explored whether the system introduced in 2015 developed engagement through an analysis of a sample of Twitter conversations. Bochel (2013) showed that e-petition systems could provide “a mechanism to enable the public to express their views to those in elected representative institutions”. Vidgen and Yasseri studied the issues raised by the UK public between 2015 and 2017 as well as the relationship between petitions’ issues and where their signatories were geographically located. And Leston-Bandeira (2019) identified four different roles for petition systems, i.e linkage, campaigning, scrutiny and policy.

Within this body of research however, recent works on the UK are relatively few in number and the perspective adopted, while making for highly valuable conclusions, is generally limited in scope and in time. No comprehensive overview of the parliamentary platform introduced in 2011 has yet been published, nor any in depth analysis of the role it played in Westminster. This is the gap which the current article means to address, answering the following question: what is the Westminster model of e-petitioning and what is its contribution to parliamentary procedures and outcomes? To answer this question, the historical background to the introduction of e-petitioning in the country will be provided as well as explanations about the functioning of the platform. Results obtained from a “distant reading” (Moretti 2013) of e-petition data from 2011 to 2022 will then be presented so as to document petition usage, both submission and signing, over the period under consideration but also the nature of popular petitions, their outcome as well as official response to petitions. The article will then highlight potential and limits of such systems and conclude with a more detailed case study of two petitions illustrative of petitions’ journey through Parliament and beyond.

The data mining and visualisations presented in part 4 are based on data pertaining to the 162,675 published petitions submitted between 2011 and 2022 made available under an open parliamentary licence by parliamentary services and collected by the author. This data includes the ID for each petition, its title, date of creation, number of signatures collected, status, rejection code, government response, debate date and debate video url. Excel was used for calculations, Open Refine for cleaning and sorting data and Tableau desktop for visualisations.

1. Historical Background

While Mosca and Santucci (2009: 121) place the origin of petitions in England in 1215, with the Magna Carta giving barons the right to address complaints to the Crown, Fox (2012: 10) refers to the reign of Richard II in the second half of the 14th century and the first petitions presented to the House of Commons. Leston-Bandeira (2018) points out that by the 15th century, the majority of petitions were indeed addressed to Parliament and evokes Dodd’s belief that petitioning played a key role in its continued existence as “a crucial outlet for the satisfaction and resolution of private interests and conflict” (2007: 325).

In 1571, a Committee for Motions of Griefs and Petitions was appointed and in 1669, the rights of petitioners and the authority of the House to address petitions were articulated in two resolutions which officially recognized the “right of every commoner in England to prepare and present petitions to the House of Commons” (House of Commons Select Committee on Procedure 2007), but also the ultimate control of such procedures by the House of Commons.

While petitioning was initially intended to address individual grievances, it progressively evolved into a tool for requesting changes in public policy and was then integrated into wider campaigns. Huzzey and Miller (2020: 125) for instance emphasized its role in supporting causes such as anti-slavery, parliamentary reform, free trade and Chartism. As the amount of time devoted to petitions in the Chamber increased significantly, the House of Commons once again reasserted control via an 1842 vote which drastically cut the number of petition debates. However, this did not deter petition usage with over 10,000 petitions regularly presented in a typical session of the 19th century. Yet by the 1970s, the figure had declined to a few dozens and the Select Committee on Public Petitions was abolished in 1974. Between 1978 and 2010, only 1,894 paper petitions a year were presented to parliament on average.1

Petitioning was revived by the introduction of the first parliamentary e-petitioning platform in Scotland in 1999 following devolutionary legislation passed the previous year. Online petitioning was then introduced in 2005 by local authorities in Kingston and Bristol and the first national e-petition platform was launched in 2006, during the mandate of Tony Blair. E-petitions were then addressed to the Prime Minister’s cabinet rather than Parliament. This platform ran until March 2011, when it was suspended in the context of the upcoming General Election.

Prior to that suspension, introducing a new platform with a closer link to Parliament had been the object of discussions within Parliament itself and between government and Parliament. From 2004, a series of reports made recommendations in favour of using ICT to facilitate interaction with the public. In 2007, an inquiry by the House of Commons Procedure Committee suggested the creation of an e-petition platform, a proposal approved on principle by the government. Matthews (2021) however highlights initial reluctance within the House of Commons to the introduction of such a tool, in particular over the possible withdrawal of the provision making it necessary to have an MP present a petition to the House and over the proposal to allow issues raised in petitions to be debated in Parliament despite the difficulty to accommodate such debates in an already very busy schedule. On the part of government, the main area for tension was the issue of cost in implementing the system.

A new platform was however launched following the change in government in 2011. Indeed, petitioning had been included in the Conservative manifesto which stated: “People have been shut out of Westminster politics for too long. Having a single vote every four or five years is not good enough – we need to give people real control over how they are governed.” (Conservative Party 2010: 66). The promise to set up a new system had also been part of the coalition agreement between the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats.

Tensions between the government and Parliament however remained until the system was remodelled in 2015. Under the new provisions, the submission of e-petitions was made directly to the House though, as explained by Matthews, “the system was governed by a Memorandum of Understanding between Government and Parliament” (2021: 416). A designated slot was allocated for debates and a new Petition Committee was created to help run the system.

2. Functioning

Prior to the introduction of e-petitioning, once a petition had been submitted, it had to be presented to the House by an MP. Before presentation, the petition was checked by the Journal Office for compliance with rules regarding the language and contents of petitions. After presentation, petitions were processed in the Journal Office and printed in the Votes and Proceedings in a supplement which appeared every Friday. Petitions were sent to the relevant Government department, which could choose to make observations, but was not required to do so. Debates were only allowed for matters of exceptional urgency, the last one being considered in 1960.

Under the current system, any British citizen or resident can submit a petition online at https://petition.parliament.uk/. The support of five signatories is requested before the petition moves on to be checked by the Petitions Committee staff for compliance with the rules regarding eligibility. The full list of reasons for potential rejection is available on the submission site and includes for instance libellous, confidential or false content. But the main requirement is that the action being requested should fall within the remit of Parliament’s activity. Once a petition is accepted, it is published on the platform and opened to signatures. Those gaining more than 10,000 signatures are entitled to a response from government while those gathering over 100,000 signatures can be considered for a debate in Parliament. Governmental response is made available on the petition site as well as a transcript and video of the debate when applicable. Each petition remains open for six months but can be closed earlier in case of a General Election when the platform is suspended.

The Petitions Committee is made up of up to eleven MPs from various parties who are assisted by administrative and technical staff. During the process, the Committee staff, acting on behalf of the Committee and following its recommendations, can ask the petitioner for more information by email or in person, ask for evidence on the issue being raised from various governmental or external individuals and organisations or press the government for action when response is deemed inadequate. The Committee staff can also organise surveys, forums, or roundtable events with experts and stakeholders. It keeps petitioners and signatories informed of the progress of their petition and of other parliamentary activity which might be related to the topic under consideration and communicates on their activity on social media. Finally, if the Committee decides that a petition ought to be debated, the team deals with the organisation of the debate. During the debate, members of the Committee present the petition and ensure it receives a response from a senior representative of government.

3. Overview of activity, contents and response

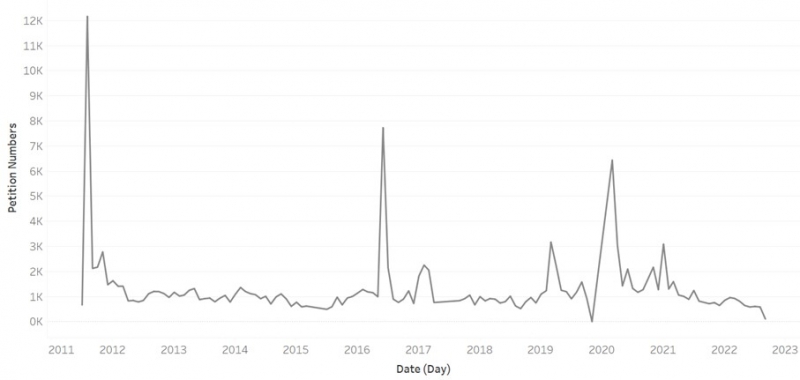

As shown by Wright (2012; 2015; 2016), the Downing Street e-petition site introduced in 2006 proved to be a very popular initiative, attracting high levels of submissions and signatures. The same can be said of the parliamentary platform introduced in 2011 and remodelled in 2015. Between July 2011 and September 2022, 162,675 e-petitions were published, with a median ranging from 31 to 35 petitions a day during the mandates of David Cameron, Theresa May and Boris Johnson. Though such figures do not include petitions rejected at the first stage of moderation whose metadata is not released by parliamentary services, they illustrate high and sustained usage since the creation of the system as shown on the graph below.

Image 1. Published Petitions Submission per Month 2011-22.

Indeed, as described in the author’s previous work (Castel 2024), peaks in activity are visible throughout the period whenever the circumstances triggered mobilisation, from the London riots of 2011 to Donald Trump’s official visit to the UK in 2016, Brexit or Covid, suggesting the platform has become a valuable tool for activism summoned when the need arises.

E-petition signing draws a similar picture, with extraordinarily popular petitions throughout the 2011-22 period.

Table 1. 10 Petitions with the Highest Number of Signatures 2011-22.

| ID | Title | Nb of signatures | Date of Creation |

| 241584 | Revoke Article 50 and remain in the EU. | 6,103,056 | 14/02/2019 |

| 131215 | EU Referendum Rules triggering a 2nd EU Referendum | 4,150,262 | 23/05/2016 |

| 171928 | Prevent Donald Trump from making a State Visit to the United Kingdom. | 1,863,708 | 09/11/2016 |

| 269157 | Do not prorogue Parliament | 1,725,630 | 06/08/2019 |

| 554276 | End child food poverty – no child should be going hungry | 1,113,889 | 13/10/2020 |

| 619781 | Call an immediate general election to end the chaos of the current government | 906,620 | 07/07/2022 |

| 108072 | Give the Meningitis B vaccine to ALL children, not just newborn babies. | 823,349 | 09/09/2015 |

| 300336 | Include self-employed in statutory sick pay during Coronavirus | 699,598 | 04/03/2020 |

| 575833 | Make verified ID a requirement for opening a social media account. | 696,955 | 19/02/2021 |

| 300403 | Close Schools/Colleges down for an appropriate amount of time amidst COVID19. | 685,394 | 05/03/2020 |

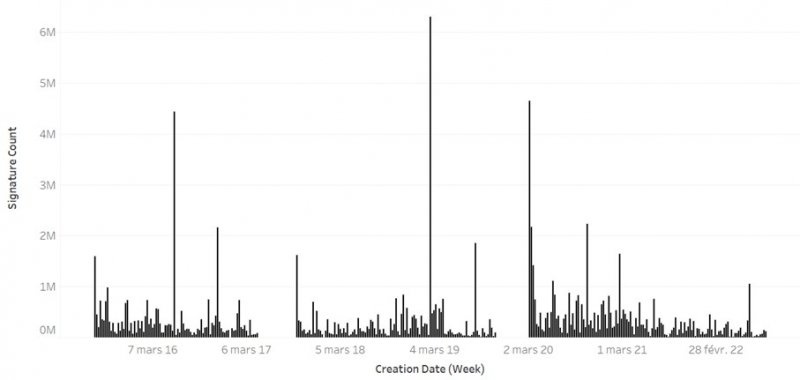

Moreover, as shown in the graph below, petition signing has remained steady, even in the last few years, corroborating the sustained popularity of the platform.

Image 2. Petition Signing per Week: 2015-2022.

Sustained popularity over such an extended period for a parliamentary e-petition platform is in fact exceptional, as was the impact in the UK of the introduction of e-petition tools on overall levels of usage compared with previous, paper-based options. Comparing usage of petition platforms is not easy as each has its own specificities. However, in their work on the petition systems of the regional Parliament of Queensland in Australia introduced in 2002 and the one of the Bundestag launched in 2005, Lindner and Riehm stated: “The available data gives no indication that the introduction of the e-petitions systems in Queensland and Germany has significantly contributed to an overall increase of petitions submitted and to an increase of the total number of signatures” (Lindner / Riehm 2009: 8). The same can be said of the French system. Between its introduction in the autumn of 2020 and the collapse of Gabriel Attal’s government in the summer of 2024, only 1,454 e-petitions were published on the site of the National Assembly, with the most popular petition (Petition 1319: Petition for the Dissolution of the brigade against the repression of violent action) gathering only 263,887 signatures.

In Britain itself, legislation was introduced in 2009, making it compulsory for all English local authorities to implement an online petitioning facility by the end of 2010. Panagiotopoulos et al. (2011) however noticed minimum institutional compliance and low actual use of e-petition facilities at the local level. As for the pioneering Scottish system, the average number of petitions published per day fell from 0,57 in 1999 to 0,07 during the second government of Alex Salmond. Despite climbing back to 0,23 during the third government of Nicola Sturgeon, the dynamics is yet one of decline with usage far less robust than in the Westminster case, even considering the difference in scale. The success of the Westminster platform is thus exceptional.

What is yet similar to all parliamentary petition platforms is the high level of rejection of petitions submitted though precise figures may vary. In the British case, between 2011 and 2022, 62.2% of published petitions were rejected, a figure which does not include, as mentioned above, petitions rejected at the first stage of moderation, suggesting rejection figures are actually higher. At the second stage of moderation, 52.1% of rejected petitions were marked as duplicates of petitions already opened on the same issue and as such, were not accepted. 24.1% were deemed “irrelevant”, a code meaning that the Committee felt the request formulated fell outside the remit of Parliament and 17.3% fell in the “no action” category meant for petitions whose request was not clear enough to be understood by the Committee. “Honours” comes next with 3.7% of petitions. Indeed, as a distinct procedure exists for nominating someone for an honour or award, such petitions are not accepted. The “already happening” (1.9%) and “no reply” (0.06%) categories introduced under Boris Johnson come last, alongside “fake name” (0.7%), used when contact details for the petitioner are missing or erroneous and “FOI” (0.02%) for Freedom of Information requests, when citizens make use of the right to ask to see recorded information held by public authorities, here again covered by a distinct procedure. The last two categories were introduced in 2015.

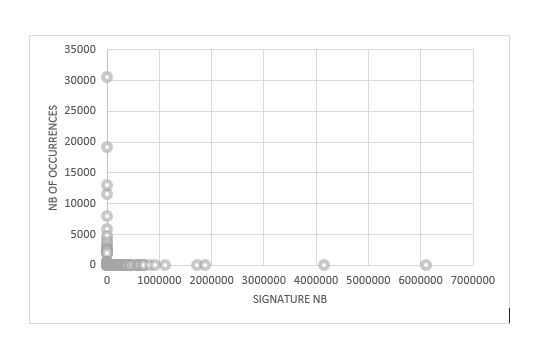

Of all petitions published between 2011 and 2022, 1,956 (1.2%) managed to pass the threshold of 10,000 signatures making them eligible for a response by the government and 343, (0.2%) gathered more than 100,000 signatures, opening the way for consideration for a debate. As shown below, the majority of published petitions (56.1%) collected 10 or fewer signatures, with only 10.3% reaching 100 or above.

Image 3. Breakdown of Petition Signing 2011-22.

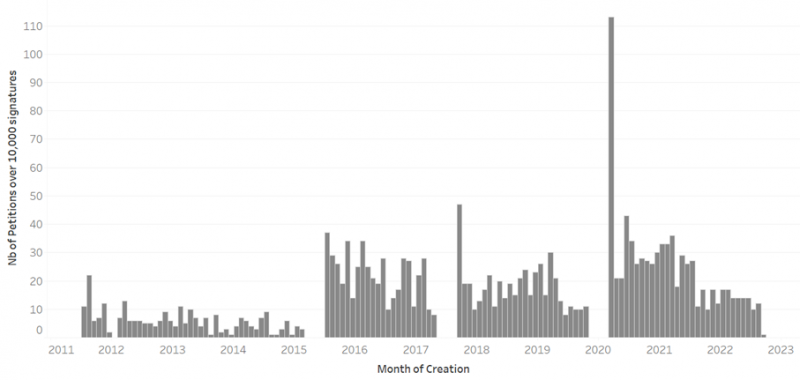

However, the number of petitions reaching the 10,000-threshold has been increasing in recent years, confirming the unwavering popularity of the platform as a tool for political mobilisation.

Image 4. Number of Petitions passing the 10,000-signature threshold 2011-22.

96.3% of petitions which gathered more than 10,000 and were eligible for a government response between 2011 and 2022 actually received one. Out of the 61 which didn’t, 57 were submitted before 2015 at a time when record keeping was less reliable and there was no committee specifically appointed to deal with petitions. The four petitions submitted after 2015 not to receive a response were all created in the run-up to the 2019 General Election which caused the suspension of the system between November 2 2019 and March 2, 2020. Overall, the promise of offering a governmental response to petitions passing the 10,000-threshold has thus been kept. The quality of response is however another matter. As shown in the author’s previous work (Castel 2023), answers are often formulaic or even copied and pasted at times, with the department in charge generally acknowledging the problem being raised but mostly sticking to an explanation of the government’s current position on the subject.

As far as debates are concerned, as data regarding them for the 2011 to 2015 period presents reliability issues, conclusions will here be limited to the 2015 to 2022 period. In this dataset, 302 petitions passed the 100,000 mark, i.e 0.29% of published petitions over that period. A debate date is provided for 300 petitions. Out of these, 247 have passed the 100,00- signature threshold, suggesting that 53 petitions did not get a debate despite reaching the required number of signatures. The most common explanation provided is that a debate on the issue had recently been organised, that the subject had already been dealt with or was being treated, or yet that the suspension of live parliamentary sessions during the Covid pandemic prevented the organisation of a debate.

Such a figure also highlights the fact that some petitions were debated despite collecting fewer than 100,000 signatures. In a few cases, the number of signatures was actually very close, as for petition 104796 (Don't kill our bees! Immediately halt the use of Neonicotinoids on crops) and its 99,909 signatures. But for most of them (39), the debate was organised, not as a result of the petition on its own but as part of a wider discussion on the issue. For instance, petition 305129 (Give non-British citizens who are NHS workers automatic citizenship) made a specific demand about foreign NHS workers but was discussed alongside petitions 300073, 301948 and 302897 as part of a much more general debate entitled “Health and Social Care Workers: Recognition and Reward” (Hansard 2020). Indeed, 108 petitions were actually debated in such a collective way.

However, in some cases, the debate seems to have been organised despite not reaching the 100,000-signature mark by decision of the Petitions Committee. For instance, petition 207616 (Insurance should be on the car itself instead of the individuals who drive it) received in January 2018 a dismissive answer from the Department for Transport: “The Government has no plans to change the motor insurance system to require vehicles themselves, rather than the use of a vehicle, to be insured” (UK Parliament Petition Site 2018). Yet two months later, the Committee organised a debate. Susan Eland Jones introduced it on behalf of the Committee with the following words:

As of this morning, 56,200 people had signed the petition. […] Observers of the work of the Petitions Committee—I hope there are many around—will note that that falls short of the 100,000-plus signatories that many of the petitions that our Committee schedules for debate receive. However, the number of signatories to this petition is still significant, especially as it proposes quite a specialist solution to a range of problems relating to car insurance. (Hansard 2018a)

Evidence thus exists of the Committee insisting on a debate when the initial answer was deemed unsatisfactory or when the merits of the issue being raised was felt to be important enough, as with petition 604509 for example (Create a “National Sleep Strategy” to end child bed poverty) despite gathering only 18,496 signatures.

Nonetheless, it is important to note that a petition debate does not lead to an immediate change in legislation. Indeed, it cannot. While the image being used to illustrate the pages of petitions which were granted a debate on the petition site shows the green benches of the main chamber, petition debates are actually held in the Grand Committee Room of Westminster Hall. And if “Westminster Hall debates give MPs an opportunity to raise local or national issues and receive a response from a government minister’, […] Divisions (votes) cannot take place in Westminster Hall” (Westminster Hall Debates webpage 2025).

4. Potential and Limits

Thus, to quote Wright on the Downing Street platform, “if they have limited policy impact, why do people bother to create and sign E-petitions?” (2016). A legitimate question if one looks for instance at the ten most signed petitions of the 2011-22 era listed above. Indeed, only two requests were actually granted and whether this might have been due to the petitions themselves is debatable. Petition 554276 (End child food poverty – no child should be going hungry) against the decision by Boris Johnson’s government to suspend free school meals in the context of the pandemic in 2020 resulted in a change of policy from the government. But the headliner for the widely publicized campaign was Marcus Rashford, a famous football player, whom Boris Johnson called personally to discuss the issue. What role the petition itself played in the success of the request being formulated and whether it was in any way decisive is difficult to assess. As for petition 300403 (Close Schools/Colleges down for an appropriate amount of time amidst COVID19), it was submitted on March 5, 2020, opened to signatures the next day and passed the 100,000-threshold on the 7th. Yet on March 9, Health Secretary Matt Hancock ruled out school closures in the immediate future. He only changed tack on March 20 after the number of casualties increased.

In some cases, no action was taken even though several petitions on the same topic passed the 100,000-threshold. For instance, there were six petitions asking for the sale of fireworks to be banned to the general public which passed the 100,000-mark between 2011 and 2022: Petition 109702 in 2015, 168663 in 2016, 201947 in 2017, 231147 in 2018, 276425 in 2019 and 319891 in 2020. In aggregate, they collected over 1,3 million signatures, a figure which does not include those gathered by the 589 other petitions on the same topic in the dataset. The Petitions Committee investigated the issue, organising several oral sessions to gather evidence from stakeholders, and released in 2019 a detailed report assessing the extent of the problem, the practical implications of a ban on public sales and use, and offering solutions at the local level (House of Commons Petitions Committee 2019a). Yet the legislation at the time of writing has still not changed. Hence the frustration expressed by Helen Jones, then chair of the Petitions Committee during the debate held for petition 231147 in 2018:

I would like to be able to thank the Minister, but in 21 years I have seldom heard a response that took so little cognisance of the debate that had just happened. We have now had three e-petition debates on the issue, yet the Government have taken no account of the public views that have been expressed time and time again. I remind them that the petitions system was set up as a joint system between Parliament and Government in the expectation that Government would take it seriously, and they clearly are not (Hansard 2018b).

It thus comes as little surprise that e-petitions should frequently be used as an example of the concept of ‘slacktivism’ or in the terms of Morozov, “feel-good online activism that has zero political or social impact” (2009). In academia, as detailed by Contamin et al. (2020) for instance, the potential of such tools to empower citizens in achieving their goals has been the object of debate. Besides, no consensus has been reached over whether they might encourage political action from previously excluded groups such as the young or people from ethnic minorities, as can be seen from the work of Carman (2014) on the Scottish system or Riehm on the German one (2014) on the one hand as opposed to Sheppard’s (2015) on Australia and Lee et al.’s on Taiwan (2014).

However, a consensus did emerge on the necessity to move away from definitions of success in terms of immediate change in policy in favour of a wider perspective as advised by Bochel, who believes that, in the case of e-petitions, “binary language of success and failure is unhelpful’ (2020: 17). Indeed, for Fox for example, impact is not limited to change in legislation: “an e-petition is certainly a way to get an issue on to or higher up on the political agenda; it is a means to attract public and media attention to the issue and can serve a useful ‘fire-alarm’ function, providing citizens with an opportunity to air their views on a national platform” (Fox 2012: 9). And for Leston-Bandeira, “although a large proportion of e-petitions to the UK Parliament are rejected and only a very small number lead to action, they nevertheless play an important role. Some have performed campaigning or scrutiny roles, but their primary effect has been to facilitate public engagement” (Leston-Bandeira 2019).

Moreover, though Matthews emphasized MPs’ concerns that parliamentary e-petitions risked undermining the relationship between themselves and their constituents, she also pointed out that 79% of those she interviewed had attended a debate (Matthews 2021: 418). As for Bochel, she argued that “petitions systems may help underpin the legitimacy and functioning of representative institutions” (2013), a notion shared by Hough:

With systems and structures of modern government becoming increasingly complex, petitions systems can help ordinary citizens navigate and engage with government and government agencies. Petitions systems provide a recognised process (often underpinned by formal procedures and institutions) which link citizen and state. (Hough 2012: 4)

Indeed, in a report published a year after the introduction of the 2015 version of the Westminster platform, the newly appointed Petitions Committee stated:

We do our best to keep people who create and sign petitions informed, not just about the progress of their petition, but also about other debates or inquiries that are happening in Parliament on the same subject. […] This has led to members of the public, who might otherwise not have been aware of these Committee inquiries, to take part.

[…] E-petition debates and other debates in Parliament which we have emailed petitioners about are some of the most watched and most read debates ever. Our emails have helped increase the readership of Hansard (the record of everything that is said in Parliament) by over 300% and the viewing of Westminster Hall debates by around 900% (House of Commons Petitions Committee 2016: 15).

While direct impact might be limited, dismissing e-petitions as mere slacktivism therefore doesn’t do justice to a system which has found such a large audience and triggered steady participation over more than a decade.

5. Case Studies

5.1 Petition 241584

The most popular petition since the creation of the parliamentary platform in 2011 has been petition 241584 (Revoke Article 50 and remain in the EU) created on February 14, 2019 with over 6 million signatures. Its description stated: “The government repeatedly claims exiting the EU is ‘the will of the people’. We need to put a stop to this claim by proving the strength of public support now, for remaining in the EU. A People's Vote may not happen - so vote now” (UK Parliament Petition Site 2019).

After the Brexit referendum of 2016, the UK invoked in 2017 Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty which provides a mechanism for the withdrawal of a country from the European Union. This set the deadline of 29 March 2019 for leaving the EU.

In the petition’s description, “People’s vote” was the name of a campaign group launched in April 2018. One of the group’s leaders, the MP Chuka Umunna, described its approach in the following terms: ‘In our democracy, it is vital that the people get their say on Brexit, rather than their elected representatives in Parliament being reduced to some rubber stamp for whatever plan Boris Johnson, Jacob Rees-Mogg, and Michael Gove have been putting together behind closed doors” (Forrester 2018). The group became the focal point of a campaign for a second referendum on EU membership which organised a variety of activities and events, and more particularly marches like the one entitled “Put it to the People” which took place on March 23, 2019 in London and attracted hundreds of thousands of participants. On this occasion, Led by Donkeys, an anti-Brexit campaign group, unfurled a giant banner with a 2012 quote by David Davis, the former Brexit Secretary, saying “If a democracy cannot change its mind, it ceases to be a democracy”. For Margaret Georgiadou, the retired lecturer who had started the petition, its genesis “lay in a screamingly frustrated anger at parliament’s dismissal of roughly half the electorate. A silent scream if you like, since those holding views counter to those in government were labelled traitors and enemies of the people” (Georgiadou 2019).

As the deadline for leaving the EU approached, the petition gathered an increasing number of signatures: 10,000 by March 18 and 100,000 two days later. By March 21, it had collected over 2 million signatures, passing the 4,5 million-mark on the 23, the day of the “Put it to the People” march. On the morning of March 21, the day after Theresa May made a speech at Downing Street (May 2019) expressing her determination to have the UK leave the EU in June at the latest, with or without a deal, 180,000 signatures were added to the petition every hour (Stokel-Walker 2019). A heat map provided by governmental services showed that signing level by constituency globally matched the votes for the 2016 referendum between Leave and Remain areas (Unboxed Petition Map 2019).

Such signing was supported by intense activity on social networks. Between the creation of the petition and March 21, the petition was shared 212,000 times on Twitter and 603,000 times on Facebook, with the help of celebrities such as physicist and musician Brian Cox or actor Hugh Grant. The petition was also signed by politicians like Caroline Lucas or Nicola Sturgeon. The rate of signing was so high that the petition site crashed repeatedly (BBC 2019).

As had been the case in 2016 for petition 131215 (EU Referendum Rules triggering a 2nd EU Referendum) and its 4 million signatures, evidence of signing via automated bots hijacking the platform was found. As described by Catherine McKinnell, then chair of the Petitions Committee, the Government Digital Service then implemented “a number of automated and manual systems to detect bots, disposable email addresses and other signs of fraudulent activity” (Hansard 2019a). Suspicious signatures were removed.

The Department for Exiting the European Union provided a first answer to the petition on March 26:

It remains the Government’s firm policy not to revoke Article 50. We will honour the outcome of the 2016 referendum and work to deliver an exit which benefits everyone, whether they voted to Leave or to Remain. Revoking Article 50, and thereby remaining in the European Union, would undermine both our democracy and the trust that millions of voters have placed in Government (UK Parliament Petition Site 2019).

The week the response was provided was actually quite hectic, with MPs taking control of the parliamentary agenda so as to vote on alternatives to the PM’s deal with the European Union. The Petitions Committee nonetheless managed to organise a debate on April 1 to discuss the issue raised in that petition but also in petitions 235138 (Hold a second referendum on EU membership, with 194,336 signatures) and 243319 (Parliament must honour the Referendum result. Leave deal or no deal, with 183,422 signatures).

On that occasion, the representative of the government, Chris Heaton-Harris, the Under-Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union, who had arrived halfway through the debate, formulated in its closing remarks an answer very similar to the one already provided in writing a few days earlier, a point already made during the debate by other Conservative MPs such as Andrea Jenkyns or Julian Lewis addressing McKinnell:

That is indeed an extremely impressive total of petition signatories. Therefore, would the hon. Member like to suggest that instead of having held the referendum in the first place, it would have been sufficient to put an e-petition in and get that particular fraction of the population voting for it, in order to set aside a democratic vote by a much larger number of people?

Let us just try this new form of democracy a bit more. Let us suppose that her party—the Labour party—gets its wish and there is a general election. Guess what? The Labour party wins and the right hon. Member for Islington North (Jeremy Corbyn) becomes Prime Minister. Then, some of us who did not like the result set up a petition and get 6 million people to say, “No, we ought to revoke that result and do it again”. Would she be satisfied with that? (Hansard, 2019a)

To which Catherine McKinnell answered:

[…] a petition does not replace our normal democratic processes. It is simply a reflection of the level of interest in this issue

and

the strength of feeling among the public, for which, as representatives of our constituents, we ought to be very grateful, as they have the means to make their voices heard—and this petition is a roar. (Hansard 2019a)

Heidi Allen then added:

I appreciate that everybody’s diaries are incredibly busy in Westminster, but I find it extraordinary that there is now literally nobody on the side of the House that is responsible for responding to the petition, given it is of such a size. Does that not tell us how poorly the 6 million people in this country who are terrified by the prospect of Brexit feel? This is supposed to be democracy—I find it absolutely startling. (Hansard, 2019a)

And indeed, the debate was attended by about fifty MPs only, some of them leaving before the end of the three hours. The conclusion of the chair of the Petitions Committee was thus subdued, expressing disappointment “in terms of engagement with the substance of the issue” and describing the contributions of the Conservatives as those at a school debating club. Voicing her support for the position defended in petition 235138 in favour of a second Brexit referendum, she concluded with the following words: “Therefore, my view […] is that we should allow Parliament to have that process, to pass it back through Parliament and give it back to the people to make the final decision. […] That is a democratic resolution to the impasse that we find ourselves in here in Parliament”. (Hansard, 2019a)

What the journey of these petitions highlights is the capacity of petitions to give an additional means of expression, beside traditional ones like marches or voting, to a wide variety of people, from ordinary individuals to MPs and celebrities coming together to make themselves heard around a common issue. Such a tool is all the more precious to users as it enables spontaneous action rather than consultation at appointed times allocated by officials, and free wording rather than the pre-defined phrasing of a referendum for instance. It also provides a clear way to track support for this issue via the number of signatures collected.

Such easily quantifiable support also provides some legitimacy to the request being made through the petition. And indeed, the notion of democratic legitimacy was raised again and again by all protagonists in the battle. Significantly, petition 241584 itself was presented as a backup plan in case “a People's Vote may not happen” and as a form of suffrage (“Vote Now”) as Georgiadou highlighted the limits of majority rule and the perceived silencing of the minority, however voluminous. As for Umunna, he contrasted the will of the people to an alleged hogging of power by a clique of ministers supported by puppet MPs, presenting marches and petitions as the reflection of a more genuine form of citizen expression.

McKinnell carefully stayed clear of such an approach, aware of the risks of putting what might be construed as mob rule ahead of parliamentary supremacy and democratic institutions. Yet she also underlined that the situation might not be as Manichean as suggested by the government’s argument of defending the will of the people expressed in an official democratic referendum against undemocratic practices. Though such an argument is constitutionally sound, her concluding remarks to the debate revealed a more complex reality, with “a referendum question put to the country that did not specify in any way how it would be delivered, and a Government who went ahead and held a general election, and lost their majority.” (Hansard 2019a) How informative of the people’s will was a binary question failing to encompass the myriad options of implementation? What mandate for decision-making on such a crucial issue might a PM with no majority in Parliament and losing the support of most of her ministers and MPs hold? Are MPs and ministers defying their PM’s authority more rightful?

Similar questions arose during the debate following petition 171 928 (Prevent Donald Trump from making a State Visit to the United Kingdom) in February 2017. On the one hand, Nigel Evans stated:

To those people who are finding it difficult to come to terms with Brexit, I say that we are leaving the European Union. That is what the people decided. To those who are finding it difficult to understand that the American people voted for Donald Trump, I say get over it, because he is President of the United States (Hansard 2017).

A statement to which Tasmina Ahmed Sheikh answered, over the noise made by the thousands of supporters of the petition demonstrating in the street outside Westminster Hall: “I have to say that I think the voices we can hear outside are perhaps more demonstrative of who we are as a country of many nations than some of the voices we have heard in here today.” (Hansard 2017)

If the views supported in petitions should be taken with the greatest caution as expressions of the voice of the people, alternatives are however not failproof, particularly in between General elections when the issue of political legitimacy has become less and less straightforward.

5.2 Petition 190627

On March 14, 2017, model and TV celebrity Katie Price submitted petition 190627 (Make online abuse a specific criminal offence and create a register of offenders) so as to try and fight the online bullying of which her disabled son Harvey was the victim. In May 2016, Harvey had taken part in the ITV programme Loose Women to talk about online trolling. A flag portraying the teenager was flown the same year at Glastonbury in support, but the abuse increased even further afterwards. In January 2017, Katie Price shared on Twitter screenshots of abusive posts tagged to her social media accounts making derogatory and racists comments about her son so as to help identify the person responsible. She then posted videos asking the troll to apologize for the numerous posts targeting her son. After the request was taken up by major media outlets such as the Sun, the person responsible was unmasked, forced to apologize and lost his job as a result. In the following months, two other persons were arrested for online abuse against Harvey.

The petition thus took what had been the fight of an individual woman to a more general level. The description of the petition indeed stated: “This does not affect just high profile people it affects everyone from every walk of life from young children, teenagers, people at work, husbands and wives. This abuse includes racism, homophobia, body shaming and a whole range of other hate speech.” (UK Parliament Petition Site 2017)

The petition was opened to signatures on March 28, 2017. Price posted a link to the petition on her social media accounts on the same day and by the end of the afternoon, it had collected over 10,000 signatures, passing the 100,000 threshold the next one. It reached a final figure of over 220,000 signatures before it was closed early due to the 2017 General Election.

In April 2017, the department for Culture, Media and Sport provided an answer on behalf of the government:

[…] While we will continue to monitor the situation, we believe that our current legal approach is the right one. The House of Lords Communications Select Committee stated in their report into Social Media and Criminal Offences in July 2014 that the criminal law in this area, almost entirely enacted before the invention of social media, is generally appropriate for the prosecution of offences committed using social media (UK Parliament Petition Site 2017).

However, a new Petitions Committee was appointed in September 2017 and in February 2018, Katie Price and her mother were invited to testify during an oral evidence session organised by the Committee gathering several victims of online trolling. This was an opportunity for Price to explain her motivation in submitting the petition:

I kept reporting people […]; these people would get closed down, but then would reopen and start again. I gathered everything together and then I went to the police. […] They arrested two people and got all their computers and mobile phones and everything, but even the police were really embarrassed because it got to a point where they could not take it any further. They could not charge them with anything because there is nothing in place, so they had to drop the cases. Since then, it has continued and got worse and worse.

[…] If I wasn’t in the public eye, I would not be sitting here now, because I would not have got 220,000 signatures in one week. So I am glad. Throughout my career, whatever people think of me—like me or hate me— this isn’t about me. I am here to protect others, and it might have taken me 25 years to achieve something, but I am glad if I can sit here and make a new law (House of Commons Petitions Committee 2018a).

On the day of the evidence session, Theresa May made a speech on public life to mark the centenary of women’s suffrage (May 2018) in which she depicted aggression on social media as a threat to democracy. Yet, though she announced that the Law Commission would assess whether the current legislation was fit for purpose in tackling those new forms of abuse, she placed the responsibility for action on social media companies, with the expectation that they should police themselves, following up on the ideas suggested in the government’s Internet Safety Strategy launched in October 2017. Such an outlook was thus far from the much more interventionist approach defended by Price, whose petition also highlighted the limits of bodies such as the new national police hub created a few months earlier to fight online hate crime and run by specialist officers as long as no binding legislation was passed to enable prosecution.

As a complex issue of global concern, the problem of online trolling was the object of attention both at the governmental and parliamentary levels before and after the petition was launched. To avoid duplicating work being done in other commissions or groups such as the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee or the Home Affairs Committee, the Petitions Committee decided to focus on the plight of disabled victims more specifically.

In February it held an open event for disabled people in Westminster to discuss their experiences of online bullying. Two more oral sessions were also held on this topic. One in April heard evidence from specialists such as Paul Giannasi, the Cross-Government Hate Crime Programme Manager or Detective Inspector John Donovan, of the Online Hate Crime Hub of the Metropolitan Police Service.

The session held in June was an interview of representatives of Facebook, Google and Twitter. Helen Jones, the chair for the session as head of the Committee, set a very firm tone in the introduction to the session, denouncing “totally unacceptable” behaviour on the part of Facebook towards various parliamentary committees, delaying the sending of requested documents or changing dates for hearing their representatives at the last minute, prompting her to say: “I want to make it very clear that your company will not be able to avoid democratic scrutiny; that it is not acceptable to try to disrupt a Committee inquiry; and that you do not dictate the terms of engagement—elected Members do” (House of Commons Petitions Committee 2018a).

Overall, the transcript for the session as well as the video, both available for public view on the parliament’s website, show strong determination on the part of Committee members to obtain answers from social media representatives through precise and informed questions clearly based on the testimonies of victims and experts gathered in previous stages of the process.

The evidence sessions provided the material for a report entitled “Online abuse and the experience of disabled people: draft recommendations for consultation” ((House of Commons Petitions Committee 2018b) published by the Committee in July 2018, examining the impact of online abuse, the responsibility for protecting victims, the capacity of existing legislation to tackle the problem, the grey area between freedom of expression and abuse and support for victims.

The recommendations were then put out for consultation. Events were held in Belfast, Glasgow, Newcastle, Swansea and London, to hear disabled people’s opinions about the recommendations. In London, all witnesses were invited to share their views directly with social media companies and the police.

As explained in the final report published in January 2019, due to the sensitive nature of the inquiry, the Committee chose to keep online engagement to a minimum. However, “Scope hosted a chat thread on their boards. The House of Commons Facebook page hosted a conversation on what people thought about making online abuse a specific criminal offence”, and an online survey was created “to allow people to give their views on the recommendations” (House of Commons Petitions Committee 2019b).

The government responded to the second report on April 3, 2019. The response readily agreed with remarks made in the report but essentially relied on existing measures and on the upcoming Online Harms White Paper as an answer. The White paper, itself in its phase of consultation in April 2019, however shied away when it was released in 2020 from the criminalisation of online abuse required by Price, relying instead on the introduction of a new statutory duty of care to make social media companies take more responsibility for the safety of their users.

A debate was thus organised on April 29, 2019 and the position of Margot James, the Minister for Digital and Creative Industries representing the government, marked a clear evolution from the one of Theresa May the year before. Indeed, she stated: “self-regulation has failed” (Hansard 2019b). Yet, she reiterated that it remained up to companies to deal with matters themselves, though under the control of a newly appointed regulator. As for legislation, she let the matter in the hands of the Law Commission, whose assessment of existing legislation was still ongoing.

The closing remarks of Helen Jones on the debate were much more positive than in the case of the Brexit-related petitions mentioned earlier: “Today’s debate is perhaps an example of how debates should be conducted in the House—civilly, and with useful contributions”. Yet she also added:

I know that the Minister takes the matter extremely seriously. However, some of the changes to the law that are required are of course not within her Department. I hope that she will convey to the Home Office the strength of feeling from the debate, particularly about the need to strengthen the legislation on disability hate crime (Hansard 2019b).

Such a conclusion seems rather anticlimactic given the time and energy spent by the Petitions Committee and the various protagonists involved in the process but is very illustrative of the difficulty to find adequate solutions to the complex problem under consideration. Indeed, in the context of the far-right riots of the summer of 2024, the limits of the Online Safety Act passed only the year before were exposed and work on this issue remains ongoing.

Price’s petition however managed to force an evolution in the position of the government on the issue of regulation of online trolling from the initial response stating that the current legislation was adequate, to the focus on self-regulation, then admission it had failed and willingness to explore alternatives. The petition thus offered a useful supplement to other forms of parliamentary action. Such an outcome is all the more notable as it resulted from collaborative work between parliamentary services and members of the public the most affected by the issue, as well as for its non-partisan approach, reflecting the mission of committees in the House of Commons to serve the institution rather than a specific party or agenda. The process is also striking in its transparency, with all steps documented and open to public scrutiny.

The voyage of the petition from its submission to the debate also highlights the length and complexity of parliamentary procedures with a layering and interconnecting of initiatives at various levels of government and Parliament. Beside her collaboration with the Petitions Committee, Katie Price also interacted with Nick Herbert, the MP from her constituency of Arundel & South Downs. He visited her home in April 2017 to discuss the issue raised in the petition, sat behind her to offer support while she testified before the Committee a year later and contributed to the debate in April 2019 with informed remarks on online bullying. Indeed, geographical data collected by parliamentary services on petitioners and signers enables MPs to find out which petitions are trending in their constituency and 81% of MPs interviewed by Matthews had attended a petition debate as a result of correspondence from their constituents (2021: 419). This evidence of an MP actively assisting their constituents in the petition process is not unique or limited to a public figure like Katie Price. For instance, Alison McGovern, the MP for South Wirral, introduced the debate on petition 62385 (SOPHIES CHOICE, smear test lowered to 16). Sophie, who had died of cervical cancer, and her family were her constituents. In both cases, calls for the common good emerged from personal experience and pain.

In the case of Katie Price and Sophie, but also on the issue of fireworks mentioned earlier and many others, the initial debate was not the end of the road. Sophie’s family and friends for example encouraged supporters to sign petition 71455 (Refusal of Cervical Screenings) submitted in 2014 and were still mobilised as late as 2021 when they supported year another petition on cervical screening addressed to the Welsh government, this time on the private platform Change.org.

As for Katie Price, she was again invited to testify (House of Commons Petitions Committee 2020) in July 2020 before the Petitions Committee which resumed work on the issue, this time focusing on the situation of people from various minorities, after the submission of petitions 239444 (Make online homophobia a specific criminal offence) and 272087 (Hold online trolls accountable for their online abuse via their IP address) on online abuse by Bobby Norris, a reality TV personality. She explained that the situation had deteriorated even further, with personalities like Ben Stokes, the England cricket captain and comedian Frankie Boyle joining in the abuse against Harvey, alongside their followers and with the advent of Tiktok. She however once again expressed her determination to protect her son and to change the law. In 2021, she launched her Track a Troll campaign through petition 575833 (Make verified ID a requirement for opening a social media account) which gathered over 690,000 signatures.

Such evidence of repeated petitions on similar issues despite the lack of direct result once again raises the question asked by Wright earlier. Why persist with such a tool? A question all the more baffling for celebrities like Price, Norris or Marcus Rashford, who have other venues for expression. A tentative answer which would need corroboration with further work may be found in Price’s recurrent statements when asked to explain her motivation: to change the law. And indeed, though Price and her supporters did not get the change in legislation they expected, they nonetheless demonstrated the inadequacy of legislation on the issue they raised and the need for an alternative. Petitions may thus be seen as the only vehicle available to citizens for reaching into the heart of Parliament so as to try and amend legislation, or at least, force an official response. The lack of an alternative could explain such persistence.

Moreover, even though the visibility of Price’s campaign undoubtedly benefitted from her status as a celebrity, it still presents similarities with more low-key ones. Indeed, petitions do not exist in a void, but are rather a cog in larger political activism initiatives and mobilising supporters from all walks of life through a multiplicity of channels, with the media monitoring the most successful ones and offering an echo resonating with the public, supporting Morva’s demonstration of hybrid campaigning strategies in the case of Change.org (2016). While further work is still needed to see whether conclusions from this case study might be applicable more globally, the example of recurring petitions like those on online trolling nonetheless suggest that petitions can indeed help citizens engage meaningfully with Parliament and that the opposite is true as well. Petitions can also help parliament meaningfully engage with citizens.

Conclusion

The current article has thus offered a comprehensive overview of the Westminster model of e-petitioning, providing historical context and details about functioning. It has also provided precise figures and statistics to illustrate the exceptional level of usage of the platform, with the number of submissions and signatures high and stable throughout the 2011 to 2022 period, an increasing number of petitions passing the 10,000-signature threshold and extraordinarily successful petitions over the whole decade.

It has also shown that though government response is indeed provided, its quality might be questionable, both in writing and during debates, despite considerable effort from the Petitions Committee. It therefore looked at answers to the apparent contradiction between such high levels of usage and such small direct impact on legislation, based on previous work highlighting the need for caution when using binary notions of success in the case of petitions and pointing at more global and diverse definitions of impact and success in this context, confirmed by the two case studies provided at the end of the article.

Indeed, the two petitions analysed further confirm the limits of accusations of slacktivism regarding e-petitions, offering instead examples of motivation and tenacity by petitioners, defending their requests through a protracted and complex process with the assistance of a perseverant Petitions Committee, and demonstrating that, though it might not be the case for the multitude of e-petitions submitted, some do actually help the public to engage with Parliament and vice versa, with the capacity to turn a “silent scream” into a “roar”. While room for improvement does exist to make the system more responsive to requests and more equipped to see change through, e-petitioning has nonetheless found a significant role and mission within the intricate procedures of the British Parliament at Westminster.