Introduction

The history of the British Labour Party has often been marked by tensions between its leadership and its grassroots, particularly in moments of ideological conflict over the party’s direction, the perfect example of this fact being the first days of the Kinnock leadership, after the defeat of 1983, when the left had been accused of being responsible for the debacle. This article contributes to the broader theme of this journal issue by examining how these tensions played out within and around Labour MPs, attached to the entryist Trotskyist organisation Militant, who got elected in the 1983 general election. The experience of these MPs illustrates both the opportunities and constraints that radical factions face within Britain’s political institutions. To fully grasp the implications of their parliamentary strategy, however, it is first necessary to situate Militant within the Labour Party and examine the internal struggles that shaped its rise and fall. Militant or “the Militant tendency” is possibly the best-known Trotskyist group in UK history. This group was labelled by the journalist Michael Crick, “the fifth-largest party in Great Britain” at its peak in the mid-1980s, with more than 8,000 members in 1986 (Crick 1986: 2). The group has a long and convoluted origin story, starting with its inception in the 1950s, when the rump of the defunct Trotskyist Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP) entered the Labour Party to merge with an extremely secretive organisation, The Club. After a few months of harsh treatment by the leadership of the organisation, the former RCP members split from The Club in 1950 and went to set up their own entryist organisation, which initially took the name International Socialism Group and then became the Revolutionary Socialist League (RSL) in 1957.

As mentioned, the RSL pursued entryism, a tactic involving the infiltration of another political party, in this case, the Labour Party, to carry out several political tasks. In the case of the RSL, it mainly involved benefiting from a broader political market to address its propaganda and finding a pool of new members to recruit (Sigoillot 2024: 185-97). The RSL’s entryism was a long-term tactic without any planned exit strategy unless a revolutionary situation emerged. The goal of the RSL was to align itself with the British working class within its natural party, identified as being the Labour Party. Then, the second step was to wait for the emergence of a politically unstable situation. In turn, this unstable situation would lead to the development of a powerful left-wing current within the Labour Party. Once these conditions were to be met, the disillusioned working class would then form a new revolutionary party, and the foundational propaganda work initiated by the Trotskyists over the years, then proven to have been right, would naturally push this new party toward a revolutionary socialist doctrine (Grant 1959).

The RSL remained relatively anonymous until 1964, when it decided, under Peter Taaffe’s impulse, to create a new journal, titled Militant, aimed at Labour members, particularly its youth. A long-term commitment to party discipline, combined with overall resilience, allowed Militant to establish itself as an influential pressure group. While the other Trotskyist groups practicing entryism left the Labour Party during the 1960s, the RSL decided to stay. From 1972 onward, the leadership of the Labour Party Young Socialists (LPYS, the Labour Youth organisation) was always held by a member of what was then known as the “Militant tendency,” enabling it to secure the LPYS seat at the Labour Party’s National Executive Committee through the years (Callaghan 1986: 196). The group also became capable of passing various motions at the party’s annual conferences, which were supposed to determine the party’s political direction. Famously, the 1983 radical manifesto of the Labour Party was the product of the militancy of both the Militant and the Tribune factions within the party. From this point, Militant became entrenched and professionalised to the extent that, by 1987, it had one employee for every 32 members (8,000 members for 250 employees), an enormous ratio. By comparison, in 2015, the highly professionalised and institutionalised Labour Party had one employee for every 1,323 members (388,262 members for 2935 employees) (Kelly 2018: 166-7), this showed the commitment of Militant to exerting an influence way above that of a simple pressure group.

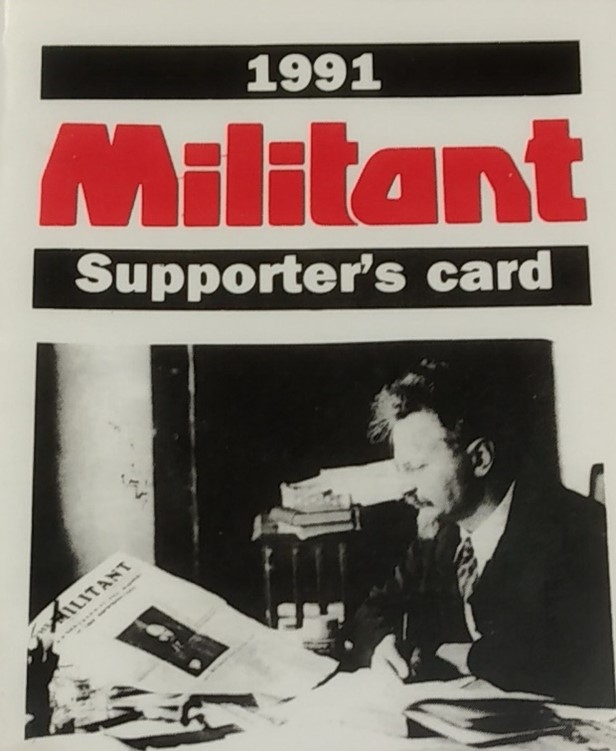

Technically, Militant avoided being labelled as a “party within a party” until at least the early 1980s by presenting itself merely as a paper whose members were just supporters of. As such, there was no member’s card for Militant members but a supporter’s card, showing a picture of Trotsky reading the American Militant paper of the 1930s on its front, emphasising its commitment to a political doctrine external to that of the Labour Party – Trotskyism – and which was essentially the same as a membership card. This ploy enabled Militant to escape most of the disciplinary measures set up by the Labour Party until a more thorough investigation in its activities was ordered by the Labour Party in 1981-2 (Hayward / Hughes 1982). Here is a picture of Militant’s supporter’s card entitled as such and showing no mention of any “membership” per se:

Figure 1: Militant Supporter’s Card. 1991.

To understand the impact and disruption that was caused by the election of Militant members of Parliament, we need to clarify some elements regarding the Labour Party itself. The Labour Party has, since its inception in 1900, always been a hegemonic party on the left of the British political spectrum. Its ideology is deeply social-democratic, as it was originally founded as the party of British trade unions after the call of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants and of the National Union of Dock Labourers to provide unions with a political representation in parliament, independent from the Liberal Party. As such, initially, the party operated as a federation of trade unions, socialist societies such as the Fabian Society, intellectuals, and even partisan organisations such as the Independent Labour Party or the Social democratic federation. This paved the way for entryist communist activity within the party, for instance, as early as 1911, the party included the predecessor of the Communist Party, the British Socialist Party. Individual memberships only became possible in 1918, when it adopted a written constitution which included the infamous Clause IV of its “aim and values” part, stating that the party’s goal was the implementation of a socialist society:

To secure for the workers by hand or by brain the full fruits of their industry and the most equitable distribution thereof that may be possible upon the basis of the common ownership of the means of production, distribution, and exchange, and the best obtainable system of popular administration and control of each industry or service. (Labour Party Constitution 1918)

The existence of this clause, along with its federative structure, made the Labour Party an ideal target for many communist groups throughout the century, who found in these aspects a source of legitimacy for their presence within it.

Entryism by the Communist Party during the first half of the 20th century led Labour to establish disciplinary measures to prevent such infiltration, notably through a list of proscribed organisations and several purges and bans for communist activists of all kinds (Klugman 1980: 59; Shaw 1987: 224). However, the 1970s saw a weakening of Labour’s disciplinary measures toward more radical ideologies (Shaw 1986: 84). The political context of the 1960s led the party to take a more liberal turn; the Communist Party had splintered into different organizations following the 1956 Hungarian crisis and was not as much of a menace for the Labour Party. Moreover, the main previous entryist organisation within the Party, the Trotskyist Socialist Labour League, had been expelled in the early 1960s (Pitt 2002). This particular political context, along with an increased liberalisation of party discipline, provided favourable ground for the remaining left-wing factions of the party, which quickly took control of the Labour Party’s annual conferences, and which partly enabled the production of the infamous 1983 manifesto “A New Hope for Britain”. This resurgence of the Labour left thus allowed the last of the entryist groups – Militant – to easily expand its activities, responding to an increased demand for more radical politics. All of this, combined with the need for a reaction to the emergence of a powerful neoliberal adversary, in the form of the advent of the Thatcher government and the defeat of the more consensual Callaghan line provided the Militant tendency with the ability to secure the election of three Militant MPs during the general elections throughout the 1980s This article will explore the impact of the three Militant MPs on British politics by examining four key aspects of their parliamentary presence. First, it will analyse the circumstances surrounding their election and how they managed to secure a foothold in Westminster. Second, it will discuss how their presence in Parliament allowed them to cultivate a strong left-wing ethos, both within and outside their party. Third, it will examine their strategic use of parliamentary sittings as a platform to propagandise their ideas, often through deliberate agitation and disruption. Finally, it will assess how their status as MPs lent credibility to extra-parliamentary actions, enabling them to amplify their influence beyond the halls of Westminster. Through this analysis, this article aims to shed light on the unique role these Militant MPs played in shaping political discourse during their time in office

1. The election of Militant MPs in 1983 and 1987

In 1983, Dave Nellist was elected as a Labour MP for Coventry South-East with 41% of the vote against the Conservatives and an alliance between the Liberal Party and the Social Democratic Party. He was re-elected in 1987, this time with 47.5% of the vote against the Conservatives, the Social Democratic Party, and the Green Party. He lost in the 1992 general election after being deselected by Labour. He then ran under the label “Independent Labour” and still managed to get an impressive 28.9% share of the vote compared to 32.6% for the official Labour candidate and 29% for the Conservatives. Although this constituted a defeat, it is worth noting that the election showed some very interesting vote shifts. When Nellist was the Labour candidate, the Liberal vote share was 25% and then 21.5%; once Nellist was removed from Labour, the Liberal vote share dropped to 9%, benefiting Labour. These figures indicate that voters were well aware of Nellist’s radical stance and the most moderate Labour voters chose to turn to the Liberal Party rather than supporting Nellist’s policies. Once the Labour Party chose to field a candidate closer to the, then, more moderate party line, the centre-aligned voters turned to Labour as their vote of choice.

Terry Fields was also elected in 1983 as a Labour MP for Liverpool Broadgreen with 40.9% of the votes against three major candidates, one from the Conservative Party, one from the Liberal Party, and one from the Social Democratic Party. He was re-elected in 1987 against a Liberal and a Conservative candidate. The same scenario occurred in 1992, with Fields, having suffered the same fate as Nellist, having to run under the “Independent Labour” label and finishing third with 14.2% of the vote, behind Labour (43.2%) and the Liberal Democrats (26.4%).

A third Militant MP, Pat Wall, was elected as a Labour MP for Bradford North in 1987 with 42% of the vote against a Conservative Party candidate and a Social Democratic Party one. Interestingly, he had run in 1983 and narrowly missed being elected, securing 30.9% of the vote compared to the Conservatives’ 34.3% in a six-candidate election. He died in August 1990, so it is not possible to draw a parallel with the others regarding the 1992 elections.

These three elections are unique in the history of British revolutionary socialist politics. Communist candidates had already managed to run under the Labour label in the 1923 elections, which was still possible mainly due to the fact that communist activists could have a dual Labour/Communist Party membership, thanks to the fact that joining a trade union automatically granted membership of the Labour Party. As we saw earlier, Labour put an end to this, and from 1924 Communist Party members could no longer be members of Labour or run as Labour candidates in general elections. From then on, no communists were ever elected as “entryists”. Among those former Communist/Labour candidates, Ellen Wilkinson and Philip Price managed to get elected as Labour MPs but only after they left the Communist Party, and Shapurji Saklatvala was elected as a Communist in 1924 after leaving Labour (Callaghan 1987: 31).

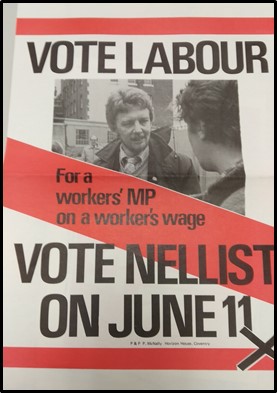

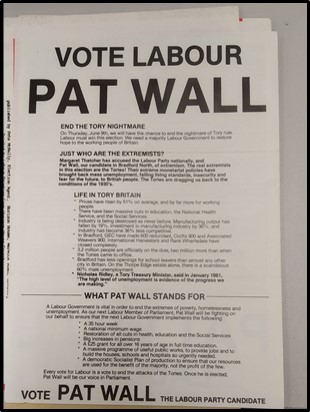

It is worth noting that the campaigns of Fields, Nellist, and Wall were in no way explicitly labelled “Militant”. Here is a poster from the 1983 Nellist Campaign (figure 2) and one from the Pat Wall Campaign (figure 3). Neither of them mentions any link with Militant. On the opposite, they strongly emphasise the fact that those candidates are Labour candidates:

Figure 2: Dave Nellist Campaign Poster. 1983.

Figure 3: Pat Wall Campaign Poster. 1983.

The journal did not particularly highlight its link with these candidates, although it was an open secret, as evidenced by the shift in centrist votes to Labour once the Trotskyist candidates disappeared and the media discussion on their subject. Militant operated with caution, toning down its links with Trotskyism in its columns. Officially, as mentioned in its subtitle, Militant was only a “Marxist paper for Labour and Youth” and not the organ of another party as had been the suggestion in numerous journals published—or directed—by entryists over the years, such as the Socialist Review (1950-62), Labour Worker (1965-8), or even the Socialist Outlook (1948-54), which were respectively papers of the Socialist Review Group, the International Socialists and the Socialist Fellowship. All these papers deployed considerable efforts not to mention Trotskyism and, in some cases, not to mention any link to any organisation. Some, like the Socialist Outlook—a journal effectively edited and led by Trotskyists—were published by the Socialist Fellowship, a Labour sub-organisation used as a front by entryists but led by Labour members, among whom were members of parliament such as Ellis Smith, Tom Braddock, Ron Chamberlain or even major figures of the institutional Labour Movement like Fenner Brockway who was the General Secretary of the ILP between 1933 and 1939 (Jenkins 1999: 91-112). As early as the 1950s, it was customary for covert Trotskyist publications to invite left-wing Labour MPs to contribute. This is exactly what Militant did in April 1988, where two MPs were given a platform in the journal, both clearly identified as not being “members” of Militant but claiming to be socialists. For example, Eric Heffer was interviewed in Militant 892 and Ron Brown in Militant 894.

Aside of those more open interviews, the election of “Militant” MPs in the 1980s was a significant focus in the journal. As mentioned in above, the journal emphasized being youth-oriented and gained a significant control over the Labour Party’s youth section. In practice, in 1983 and 1987, some funds of LPYS were used to charter buses and conduct strategic door-to-door campaigns in constituencies where a Militant candidate was running. Therefore, the journal and the LPYS financial resources were mobilised for certain candidates more than others, making the slogan “Vote Labour” a form of disguise for their true intent. However, all this was fair game, and Labour has always had subgroups and tendencies within its walls and liked to describe itself as a broad church. What is unique here is the extent of the scale of the operations and total domination of Militant over the LPYS’s militant force. The organisation was structurally an ideal audience for the Marxists, with its young activists usually in demand of more political training, easily mobilised, and intensively engaged.

This leads us to the question of the nature of the parliamentary action of those revolutionary socialist members of Parliament who were elected as members of a party which is theirs only on paper.

2. The creation of an ethos

As we have seen, the campaign of Militant MPs was oriented towards a socialist program with slogans like “A Workers’ MP on a Worker’s Wage,” emphasising ideas of class struggle and the need for Marxist policies. In an interview the day after his election in the Militant journal on June 17, 1983, Dave Nellist even used this expression himself:

As a workers’ MP on a worker’ s wage l will stand shoulder to shoulder with all the struggles of working people politically and industrially to fight to defeat any attacks by this Tory Government on our class (Nellist 1983)

This emphasis on Nellist’s worker’s status and the symbolic retention of a link to the working class through the “worker’s wage” helped establish the Militant MP in a strong working-class ethos. The corollary of this setup is the legitimisation of the traditional communist critique against Labour Party leaders: the problem has never been at the level of activists and party members but rather at the leadership level, which plays into the hands of the bourgeoisie by keeping the masses in blind trust in the parliamentary system. This tactic is as old as the birth of the Communist Party of Great Britain in 1920, when Lenin recommended the affiliation of the Communists to the Labour Party in order to make them appear as the “true” leaders of the working class, that always fought alongside them while the Labour Leadership, once in power, would betray them in favour of traditional bourgeois politics.

The symbolism is strong: it is about taking power and exercising it without elevating oneself socially. Of course, MPs have fringe benefits, but the issue of wages is not overlooked, and this approach keeps Militant MPs symbolically and practically “in the workers’ camp.” By doing this, they do not belong to those Labour MPs who “betray” or pursue a career plan. This ethos is still conjured, today, by Dave Nellist, who remains a frontman for the Socialist Party, the direct descendant of Militant.

Terry Fields used this ethos in his interventions in parliament to build an “us versus them” rhetoric, placing him at the vanguard of the Labour Party, creating the image that he could push for the Labour Party to adopt a more radical stance. The following intervention during a vote on the adjournment of the activities of the house is a clear example of that rhetorical device:

For my part and on behalf of those who are active and worried about the Health Service, I can only put forward as a solution to the problems of people in need of hospital treatment part of that resolution, which we will fight democratically to have included in Labour’s programme. The resolution called for the deprivatisation of all privatised services in the National Health Service and for all lost jobs to be replaced. It also called for the abolition of all charges for health care, the abolition of the private health sector and the nationalisation of the pharmaceutical industry, placing it under democratic control and management with compensation to be paid only on the basis of proven need. Those things are the only solution to the problems of the Health Service, and I shall be campaigning for them while Tory Members will be sunning themselves all over the globe. (Hansard 1986)

In this extract Terry Fields is able to both discredit parliamentary action and Tory inaction while appearing as, first and foremost, an activist: he would continue campaigning and fighting for the people while the other members of the house would take their vacations and stop caring about others. This denunciation is perfectly in adequation with the Marxist belief that parliamentary activity is a sham and is not a solution in itself to the workers struggle. As such, a revolutionary MP should take every opportunity to expose this state of fact to the population and use their elected position not only as a tool to influence legislation but to embody their struggle with the system by pointing, from within, the inefficiency of bourgeois democratic institutions in defending the working class.

From the point of view of their action in parliament, we can affirm that the activities of the entryist MPs bore a strong symbolic significance, and the participation of Militant MPs in parliament was real. We can mention the high number of interventions by Dave Nellist, who seemed to play the exemplary MP card more than his comrades, with 494 interventions (with a peak in between 1987 and 1992) compared to 134 for Fields over the same 9-year period and 67 for Wall over 2 years1. The speeches given by Militant MPs covered social security issues, foreign policy (with significant participation in related committees, directly linked to the internationalist aspect of Trotskyism), and industrial issues, especially during the 1984-5 miners’ strike. Ironically, it is worth noting that Dave Nellist was even crowned “Backbencher MP of the Year” by the right-wing political magazine The Spectator in 1991.

3. Agitation within Parliament

Dave Nellist knew how to use parliament not by following its rules but by abusing them. For example, during the April 13, 1988 debate on examining the effects of legislative changes made to social security, Dave Nellist interrupted the Secretary of State for Social Services, John Moore, during one of his speech 11 times, by standing up (which is the proper way to ask for the floor).

His behaviour required the intervention of the Speaker of the House, who told him to stop disrupting the session. Nellist replied with the equivalent of a procedural reminder:

Not at all, Mr. Speaker. My point of order is that if I rise every minute or every two minutes to ask the Secretary of State to give way, that is my perfect right as a Member of Parliament to try to put my point of view. This is the only chance that I get to ask the Secretary of State questions (Hansard 1988)

After this point and other reminders from the Speaker of the House of Commons, a vote to expel Nellist from the session was decided, with 271 votes against 32. The bulk of support for Nellist came from the Socialist Campaign Group of MPs, with notable left-wing Labour figures such as Diane Abbott, Denis Skinner, Ken Livingstone, Jeremy Corbyn, Eric Heffer, and Tony Benn. Nellist responded to his eviction defiantly: “I shall be back.” (Hansard 1988)

Strong invectives were used against the Conservative Party throughout the terms of the three MPs, following the purest tradition of the far left. The parliamentary work of Militant MPs thus contributed to legitimising a national political opposition to capitalism, regularly mentioned as such within the House of Commons, which was then relatively marginal or even non-existent in Great Britain. The introduction of class struggle rhetoric and the fight for a communist society characterised all long interventions by Militant MPs. Nellist was a frequent user of fiery rhetoric in the House of Commons, as shown by the following intervention on the subject of the Gulf War:

In a number of meetings that I have had since 2 October, opposing the Government’s support of possible war, I have begun each of those meetings as I begin my speech this morning, with a condemnation of the invasion of Kuwait by Iraq and the taking of hostages. I should have thought that that would go without question. However, the speeches that I have heard from leaders from all sorts of countries have the stench of hypocrisy. I think that it was Disraeli who said that a Tory Government was organised hypocrisy, so I suppose that I should not be too surprised. (Hansard 1990)

It is also interesting to note that the attitude of Militant MPs in parliament was perceived as unevenly disruptive. In November 2020, during an interview conducted with Neil Kinnock2, the Leader of the Labour Party at the time, the latter confided that while Terry Fields had an “inappropriate attitude,” Dave Nellist appeared to him as a “very hardworking, diligent MP” about whom he had “reservations regarding his exclusion from the group.” (Kinnock 2020)

4. Agitation outside Parliament

Clearly, in Marxist-revolutionary theory, parliament is not a suitable tool for positive social change in favour of the working class’s interest. Militant, therefore, directed its MPs (referred to, in its columns, as “socialist MPs”) to spend as much time agitating within the country as within parliament, reducing the latter to a platform for promoting socialist ideas. It is evident that the Militant MPs were aware of this directive, their parliamentary activity was extensively covered in the journal only to establish a link between its audience (the working class) and its representatives (the Militant MPs) in order to make the former understand the importance of gaining a revolutionary national representation.

This idea of giving the working class a “real voice” (contrary to that of reformist Labour MPs) is exemplified in an article of Militant number 662, in which Martin Lee makes an account of a Militant Rally in Manchester in which Terry Fields intervened to explain that the true instrument of change was not parliamentary activity but revolutionary agitation:

The fact that 220 Labour Party activists and workers turned up to the meeting showed that workers are now beginning to sense they have a real voice in parliament. Instead of evasion and vague statements, Terry’s comments were sharp and to the point. When asked what MPs could do in parliament he pointed out that real power lay outside of parliament and in the organisations of the working class. (Lee 1983)

Terry Fields always made a case of distancing himself from the Parliamentary Labour Party. At a public Militant congress in 1985, Terry Fields began his speech with the following words:

Comrade Chairman and comrades... I’d like to bring you fraternal greetings from the Parliamentary Labour Party... [pause and laughter in the room] I’d like to [more laughter in the room]. I’d like to bring you fraternal greetings from the Campaign group of MPs... well… those of them who are not after jobs as bag carriers for Neil Kinnock and some of the Shadow members of the Cabinet. (Socialist Party 2011)

Of the three MPs, it is perhaps Terry Fields who caused the most significant agitation outside parliament, linking it to his own parliamentary activity. Indeed, Militant played a central role in the fight against Margaret Thatcher’s poll tax by its major contribution to the establishment of the All Britain Anti-Poll Tax Federation, a national coordination led by Militant entryist member Tommy Sheridan. One of the main actions undertaken by the Federation, aside from demonstrations, was organizing a non-payment campaign, in which a significant portion of the population participated. Figures put forward by Peter Taaffe, Militant’s leader, mentioned 18 million people (Taafe 2013: 431). A researcher, Richard Bellamy, reported that 38% of eligible Scottish taxpayers and 25% of their English and Welsh counterparts refused to pay (Bellamy 1994 : 22-41).

Terry Fields was one of the prominent figures of this campaign, with his union, the Fire Brigades Union, being one of its main instigators. He used his status as an MP to bring the refusal to pay the tax to the forefront of the political scene by participating himself. This resulted in his imprisonment for 60 days and accelerated his exclusion from the Labour Party. In reaction to his imprisonment, Neil Kinnock stated that the Labour Party did not support this action and that “lawbreakers must not be lawmakers” (BBC 1991).

It was the exclusion of Terry Fields and Dave Nellist that ultimately enabled the most significant extra-parliamentary activity related to their mandates: once the Trotskyist MPs were expelled from the party in 1991, a campaign to defend their right to remain within Labour was launched, involving demonstrations, leaflet distributions, and even the solicitation of other MPs, notably those from the Socialist Campaign Group, to intervene at gatherings and defend Nellist and Fields. The campaign’s central question was not their individual right to stay within the party but rather couched in the question: does the Labour Party accept Marxists within its ranks? This, in turn, raised the traditional question in the rhetoric of the British revolutionary left: is the Labour Party leadership truly on the side of the workers? Therefore, the practice of parliamentarism allowed the Militant group to highlight the traditional Trotskyist arguments that parliamentarism is a dead-end and that the Labour Party leadership works against the working class, and that only the revolutionary party/organization can lead the struggle.

In this context, the phrase by Fields, “I’d like to bring you greetings from the Parliamentary Labour Party,” (Socialist Party 2011) takes on its full meaning. The parliamentary Party (and not the Labour Party itself) is not capable of defending the class’s interests—the only effective solution would be to regain control of the party by breaking away from its leadership, as theorized by Ted Grant, the thinker behind Militant, in 1959 in the practical foundations of the RSL, specifically the pamphlet The Problems of Entryism.

Ultimately, for the Trotskyist group, access to parliament served two purposes: a platform function and a legitimization function. The political object and the institution of parliament are thus subverted and lose their legislative function under Trotskyist practice.

This conclusion is not general because it only represents one part of the picture. Indeed, Militant never had MPs while the Labour Party was in government. As such, the dual Labour/Militant membership did not cause significant blockages at the Labour group level, because party discipline mattered less. Therefore, Militant MPs did not form a distinct parliamentary group capable of using parliament for purposes other than extra-parliamentary ones. This may also explain the support for Militant from most members of the Socialist Campaign Group of Labour MPs, who consequently opposed the “witch hunt” against Militant during the 1980s.

Nevertheless, the presence of Militant MPs certainly concerned British intelligence services, which actively investigated Nellist and Fields. MI5 is said to have gone so far as to infiltrate Militant, reportedly recruiting around thirty “double agents” placed within the MPs’ entourage. The Merseyside Police claimed in 2008 to have collected information on Fields for the intelligence services. According to Oliver Price and George Kassimeris, two researchers specializing in British intelligence, a former intelligence officer admitted that MI5 “requested its West Midlands branch to infiltrate the Coventry Labour Party to monitor Nellist when he was an MP” (Kassimeris & Price 2021). The agent was instructed to “cultivate” Nellist, “develop a close relationship with him, assist him with many tasks, and accompany him to numerous meetings.”

The two authors stated in their recent research that Militant was considered a subversive threat to the state itself from the late 1970s and early 1980s (notably in 1983, Militant’s peak influence within Labour). Militant was monitored as subversive, just as the Communist Party had been from the 1920s to the 1960s. No other Trotskyist group had ever been characterized as such, most being monitored only for their participation in public order disturbances (like the International Marxist Group and the International Socialists in the 1960s).

It was the iron discipline and unity in action that allowed Militant to make its nest within local Labour parties and become capable of imposing its choices for candidate selections in local and general elections, even if it meant relocating members to register in other constituency Labour parties.

Conclusion

The experience of Militant MPs illustrates that while Parliament serves as a crucial institution in democratic governance, it is also susceptible to other uses by fringe movements. The involvement of Trotskyists in Westminster ultimately highlighted the constraints of traditional parliamentary politics in resolving deep-rooted ideological disputes, especially when dealing with actors whose goals extend far beyond the usual scope of policy-making, illustrated by the expulsion of Fields and Nellist from, not only the Parliamentary Labour Party but also of Militant members from the Labour Party in general. The legacy of this period remains a pertinent case study in the broader conversation about the role of radical ideologies in democratic systems and the ongoing struggle to define the boundaries of acceptable political discourse within major political parties.