This article studies the specific modes of visibility of housing in the Black radical press of the 1960s and 1970s, and how this site relates to violence, which it makes tangible in the landscape. The Black radical press refers here to the two bi-weekly or weekly newspapers published by the Nation of Islam (hereafter NOI) and the Black Panther Party (hereafter BPP): Muhammad Speaks, published from 1961 to 1975, and The Black Panther Black Community News Services (hereafter The Black Panther), later renamed The Black Panther Intercommunal News Service, published from 1967 to 1980. The function of these publications was to spread the alternate worldviews of the two major Black radical organizations of the period. The Nation of Islam, created in the 1930s and headed by Elijah Muhammad, combined Islam and Black nationalism; it had grown into a working-class mass movement after Malcolm X became a prominent figure of the organization in the 1950s, criticizing the integrationist approach of the Civil Rights movement. The Black Panther Party was a Marxist, revolutionary group founded in 1966 in Oakland, California (in the wake of Malcolm X’s assassination), out of the perceived need for self-defense from police brutality. Both organizations’ publications combine reports of systemic exploitation, news about the organizations, and their agendas (a formal program of ten points reproduced in issues of The Black Panther, and a more mobile, and often sermon-like, corpus of slogans and images deployed in Muhammad Speaks in a special feature comprising around eight pages from the late 1960s on). They stand out in their media context, as each had a very large circulation: at their peak, 600,000 for Muhammad Speaks in 1972 and over 100,000 for The Black Panther in 1970 (Wolseley 1990: 90; Raiford 2011: 180). In terms of their content, they developed specific editorial styles, with images playing an important role. This, combined with the importance of editorial or opinion content, made them “quasi-magazines” according to Roland Wolseley in his survey of the Black press (1990: 90, 141).

So far, their “visually dominant newspaper style” (Doss 2001: 179) has been studied only for The Black Panther, where artist Emory Douglas (the BPP’s Minister of Culture) was visual editor, both responsible for the layout and contributor of images (Rhodes 2007: 91-115; Raiford 2011: 177-204). This publication combined photographs and numerous drawings (especially images of guns, panthers, and policemen as pigs) (Duncan 2016; Gaiter 2012; Gaiter 2018). Meanwhile, Muhammad Speaks has been analyzed mostly in terms of its text contents, for example the sections devoted to the alternate way of life promoted by the NOI or the articles penned by women (Gibson 2015; Jeffries 2014). It has also been approached in relation to its editorial structure (Wolseley 1990; Helgeson 2014; Carroll 2017) and mode of distribution. Both papers were indeed central to their organizations’ memberships and finances. And yet, images were also key to Muhammad Speaks, a publication addressing a readership with various levels of literacy and trying to redirect how African Americans viewed themselves and the white power structure. Images functioned in similar rhetorical terms to the text content: celebration (of Black beauty and Muslim discipline, of development in decolonized and non-aligned countries), and denunciation (of violence and exploitation, of imperial wars)—these two angles being an integral part of “a self-consciously counter-hegemonic picture of the world,” meant as “radical truth-telling” (Helgeson 2014: 215).

This article argues for including these two activist publications in the study of the uses of visual and especially photographic materials by African American militant organizations—as Leigh Raiford (2011) has done with the BPP alongside SNCC. Based on the study of all issues of both journals in digitized and/or microfilm form, it focuses on a particular category of images that were strongly and continuously published in both periodicals, often in striking visual forms: images of housing. It is important to note that this overview began with visually scanning undigitized microfilms of Muhammad Speaks, and the method of research was therefore not keyword search but direct visual recognition of houses, porches and interiors. This qualitative form of research, reliant on human attention, identifies legible images—photographs that look like housing, and often like houses— at a glance. They signal a distinct presence of housing in the pages of these publications. The images are also not extracted, but approached as part of newspaper pages and whole issues, as they were related to distinctive themes of the organizations and publications (such as genocidal socio-economic conditions). This paper explores how a media discourse is constructed in both intensive and extensive ways—in the discursive power of visual and textual arrangement on specific pages, and in the cumulative effects of certain tropes (in images, but also in words used in captions and article).

Housing was an important focus of both organizations: for the BPP, it was an aspect of inequality (alongside food and access to healthcare), and more specifically of the state of siege that Panthers denounced in African American neighborhoods (alongside police harassment). It was also point number 4 of the party’s 1966 program, titled “We want decent housing, fit for the shelter of human beings.” For the NOI, housing was a category of the “clean living” promoted by the organization, and in its extant form a materialization of the subordinate place assigned to African Americans in the United States. The main focus of the NOI’s discourse of separatism was on land, and what would be needed to create the conditions of independent life for African Americans: “good homes,” farming land and machinery, industries and hospitals. While the NOI promised suburban-style houses if African Americans channeled their energies towards building “a world for self” away from Whites, the BPP advocated for cooperative housing. Though those outcomes were different, as envisioned by two organizations following divergent strategies (Black revolution vs. Black nationalism), the then-current housing conditions (rural wooden houses, rickety back porches, squalid apartments with lead paint) were relentlessly denounced by the images published in both papers. And if the examination of all images related to housing in the two publications reveals Muhammad Speaks’ distinctive, though not exclusive, focus on the rural southern wooden house, while The Black Panther paid more attention to the substandard interiors or the back porches of multi-family buildings in the urban neighborhoods that were the focus of the BPP’s local chapters’ community programs, both publications had a national coverage of socioeconomic conditions—with housing, and its distressed materiality, a micro-geography of national importance.

During the 1960s and early 1970s, racial crisis and conflict appeared to move from Southern states, with the Ku Klux Klan still burning crosses and rural voters being registered, to Northern and Western ghettoes, where the urban crisis, riots, and decaying ghetto conditions redefined racial issues. This geographical shift also implies distinct residential typologies, from the agricultural to the urban. Out of the two publications under study, Muhammad Speaks is the one that straddles almost the entire decade of the 1960s: published out of a major Northern city (Chicago), it always covered both Northern and Southern sites and struggles and it did not separate political disfranchisement from poverty. This corresponds to the definition of the Civil Rights Movement as not confined to the South, which has been acknowledged by recent historiography. As this article will explore, in the Black radical press the spectacle of housing implied a national geography of structural violence that was continuously imposed on African Americans. And while this reading of the poor dwelling as violence was most radical in Muhammad Speaks, where it was presented as the materialization of genocide, Muhammad Speaks and The Black Panther will be considered in parallel throughout this article because they each capitalized on housing as both visible social conditions and a space intrinsically linked with externally imposed violence.

The iconography of ill-housing is so strongly associated with a mainstream, middle-class, reformist gaze (Stange 1989b) that it is useful to sketch an alternative genealogy. The article will briefly go back to the 1941 book 12 Million Black Voices, as a left-wing Black phototextual indictment of racism across the land, which constitutes a precedent for the way the Black radical press of the 1960s made use of housing photographs. It will then outline how images of dwellings encapsulated landscapes of violence in a form that was easy to insert on the newspaper page, and how iconotextual combinations scripted housing as the tangible form of structural and diffuse violence. The comparison between the treatment of residents in the images published by Muhammad Speaks and The Black Panther also reveals divergent treatments of agency and resistance: fighting back from the home is central to Emory Douglas’s images for The Black Panther, while in Muhammad Speaks the existing shack can only work as a foil for the desired future of wealth and independence—at the expense of residual integrity for the figures of dwellers in the photographs. The sustained and different focus of each journal on images of housing suggests how plastic this site/sight can be for a gaze that aims at contesting and transforming the present.

1. Housing photographs and crime narratives: 20th-century Black voices

There is a rich US history of photographing housing as not just an element of decor, but rather as a destructive force. Since Jacob Riis’s photographic exposure (1890) of “how the other half lives” in the Lower East Side, substandard housing has been visualized photographically as a cause of disease, the source of adverse and dangerous cultural effects, and a factor of crime. In keeping with an older urban visual culture, the middle-class audience and readership of Jacob Riis was led to view the slums not just as a place of misery, but also as a site of locally generated violence that threatened to spill over into the rest of the city (Stange 1989a). Such a vision was reactivated in what became a massive mid-twentieth-century drive against slums and blighted areas, alongside a more socially-minded vision that focused on the suffering inflicted by overcrowded, decayed and dangerous housing on the residents of poor neighborhoods (Zipp 2012).

But the most striking visual genealogy for the treatment of housing in the 1960s in the Black radical press is to be found in Richard Wright and Edwin Rosskam’s 12 Million Black Voices (1941), which also recodes substandard and overcrowded housing as violent crime on both ends of the South-to-North Great Migration1. Drawing on the Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographic file, this phototext follows African Americans from Southern fields, complete with broken porches and burning shacks, to Northern ghettoes, with their overcrowded and decayed apartments. The Southern rural and Northern urban sections contain echoing images, such as children asleep in barren rooms (1941: 63, 84, 85, 107). Additionally, in the binary structure of the book, the threshold between rural and urban spaces is residential: the middle section, entitled “Death on the City Pavements,” opens on the title printed over the ramshackle back porch of a Chicago three-story tenement, standing tall on the page (1941: 91). This is followed by a section on the housing conditions inflicted by the “bosses of the buildings,” a formula echoing the “lords of the land,” with the famous pages structured by the anaphora “The kitchenette is…” at the beginning of each paragraph (105-111). The most famous of these stanzas declares that “The kitchenette is our prison, our death sentence without a trial, the new form of mob violence that assaults not only the lone individual, but all of us, in its ceaseless attacks” (106). As established by Paula Rabinowitz, Richard Wright was influenced both by newspaper exposés of housing conditions in the South Side of Chicago—he collected clippings on this subject among others in the late 1930s (Rabinowitz 2001: 111, 115)—and by true-crime magazines; he fused these different sources in what Rabinowitz terms “documentary noir.” It is in fact striking that the book’s version of the key 1930s documentary scene of the poor dwelling, where newspaper pages are used as wallpaper (Hills 2011: 229-231), illustrates here the text’s segment that focuses on the love of books among the young dwellers of such housing (Wright and Rosskam 1941: 63). In the photograph, newspaper pages are used not just as wall papering but also as tablecloth on a table where five youths are gathered, all reading books, in a striking visual alignment between media culture (including books by Wright and Rosskam) and poor dwellings. As Rabinowitz puts it, the book

supplements the crime narrative—or, better, inverts it—to make clear that the crime, that which the American people, or at least white Americans, had been lied to and been lying to themselves about, was the crime of slavery and its attendant Jim Crow laws and culture of racism. This was the true crime story. (Rabinowitz 2001: 108)

And as suggested by the layout of the “Death on the City Pavements” page, where the silhouette of housing stands as both a site and a figure, housing conditions are a key contemporary instrument of this crime. Quite logically, on the next pages, they are shown and described as actively pressing upon the bodies that inhabit them.

The South Side of Chicago, a site of overcrowding, segregation, and housing-related deaths (including by fires or the collapse of back porches), is indeed famously central to this phototextual narrative, which offered the most significant publication of FSA photographer Russell Lee’s photographic work in that city in 1941 (Stange 2003; Natanson 1992). But Wright and Rosskam’s book is significant less in terms of the photographic material per se than in its selection, sequencing, and pairing of the images with text; and the first segment of this migration narrative also includes a strong focus on Southern rural housing conditions. In the book as a whole, there is thus an insistent focus on domestic spaces in various African American geographies, and the association of decay with death is strong, throughout the book and national space; doesn’t the silhouette of a light-colored pile of rubble in a Chicago empty lot photographed by Russell Lee (Wright and Rosskam 1941: 114) echo the round shape of the earth tomb photographed by Walker Evans in Alabama (55)? The book’s association of violence, housing, and racial inequality signals a distinct Black radical voice in the photographically saturated media of the middle decades of the twentieth century—with housing photographs positioned in a different genealogy from that of mainstream reform photography: housing not just a factor of criminal activity, but as racial crime.

In the years after World War II, the intersection of crime and housing would take a more literal form, especially in Chicago—that city being both the main northern geographical focus of 12 Million Black Voices and the home of the Johnson Publishing Company (with its two key African American magazine publications, Ebony and Jet, respectively founded in 1945 and 1951) and later of Muhammad Speaks. In the late 1940s and 1950s, Chicago’s residential areas became the field of an urban guerilla war with both mob violence and individual attacks on homes, as African Americans tried to move out of overcrowded neighborhoods into houses and apartments in the South West of Chicago (Hirsch 1998; Smith II 2012). Ebony belatedly covered the subject when it published a six-page photoessay on the neighborhood violence that was set off in South-West Chicago by the 1953 arrival of an African American family in the public housing development of Trumbull Park (“Riot Victim” 1954). Adam Green has suggested that the coverage of that crisis in Ebony in 1954 mediated this housing project for the African American audience of the Johnson press as a site of communal contemplation of Black domesticity under threat (Green 2007). But as a group that until the mid-1960s was mostly focused on Black middle-class success and depended on advertising revenue (in contrast with The Black Panther, and with Muhammad Speaks where only Black Muslim businesses advertised), the Johnson press generally provided little coverage of violence and poverty (Stange 2001)2. By contrast, these two themes were a major focus of Muhammad Speaks and The Black Panther, next to both organizations’ affairs and international news. And Wright’s steadfast denunciation of housing conditions and violence in 12 Million Black Voices resonates with the way Muhammad Speaks and The Black Panther covered housing as criminal evidence, and more specifically in their visually charged treatment of this nexus of housing and violence.

2. Everyday sensationalism? Dwellings as visual material in Muhammad Speaks and The Black Panther

In this section, I focus on the way a certain basic photogeneity and legibility of houses is worked into newsworthiness in both Muhammad Speaks and The Black Panther. These publications often used images of architectural structures to illustrate situations of violence, both violence directly targeting the architectural structure of the pictured house and more generic situations of oppression. I return later to the coding of houses as landscapes of violence, but to establish images of housing structures as a photojournalistic trope in both publications I first outline how they come to feature in the newspapers, in terms of subject matter of articles, of the sourcing of images and of the layout of pages.

The house under attack (usually a wooden house in a residential urban environment) is central to the early issues of The Black Panther, which was started as a news organ for the party and naturally reported on the numerous police attacks on the premises of city-level BPP chapters. This was often showcased in a visually intensive way—either through detail or accumulation, with a close up on bullet marks or with spreads showing only captioned photographs of impacts, shattered glass, burned out window frames (“1218 28th Street,” The Black Panther, April 6, 1969, p. 9-11), and sometimes neighboring homes blasted in the bombing of a BPP chapter (The Black Panther, May 11, 1969, p. 2-3). The structures attacked were political bases, but they looked like the rest of the neighborhoods where they were established, with wooden frame houses (see The Black Panther, September 20, 1969, p. 3 or December 11, 1971, p. 3). And this visual coverage also included homes of non-Panthers targeted by the police, as in the two photographs of bullet-riddled window and door which framed the photograph of a woman and her children in an article by the Illinois chapter of the BPP, entitled “Chicago Gestapo Attacks Residents of Altgeld Gardens Community” (The Black Panther, April 10, 1971, p. 5). When this type of illustration peaked after December 1969, with multiple publications of the photographs of the Chicago apartment where Fred Hampton and Mark Clay were shot to death by the FBI and the Chicago police, the central image was that of the stained mattress where Fred Hampton had bled to death—an eminently private space memorialized as the absence of sanctuary (The Black Panther, December 13, 1969, p. 15; September 18, 1971, p. 6). The photographs of attacked chapters also stand out because they are most often records of specific material injuries. These are procedural images, such as could be included in a legal file or a complaint. The same type of images is regularly used to illustrate articles about “inhuman” or “indecent” housing; the photographs of problematic housing situations (regularly included in the newspaper after the party’s turn to community programs in 1969) focus on objects and surfaces as often as on lived spaces. Images that illustrate specific housing code infractions, with a distinct vernacular quality, thus make their way in the newspaper. These pictures were presumably provided by local groups working on denouncing certain housing conditions in specific buildings; they are grassroots images. And beyond photographs, the visual texture of distressed housing is also developed in many of Emory Douglas’ back covers—with peeling, cracked or unplastered walls, cockroaches and rats, hammering a visual motif of poverty and harassment (rats are also used in the paper as animal equivalents for landlords and capitalists)3.

The simplicity of many of The Black Panther’s photographs of domestic surfaces, and the distinct journalistic treatment that turns them into newsworthy material by pairing them with the fourth point of the program (“We Want Decent Housing Fit for the Shelter of Human Beings”), can be compared with Muhammad Speaks’ reliance on simple photographs of single houses. Including a picture of a house where an event took place or where a protagonist (victim or perpetrator) lives, is one of the journal’s basic illustrative formulas, an element of décor almost like a headshot. Sometimes, the house photograph is one ingredient in a sort of micro-photoessay (one house, one portrait, one group portrait, for instance; or, one house, one accessory, one portrait).

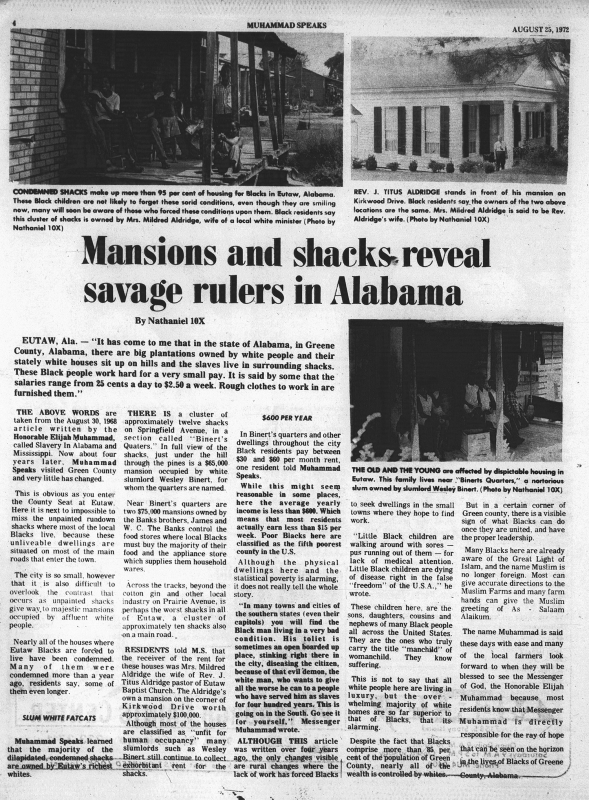

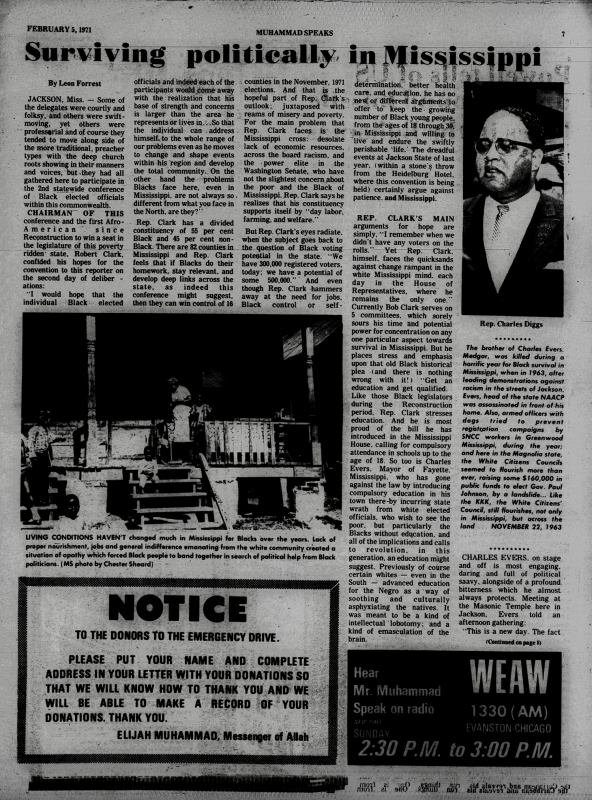

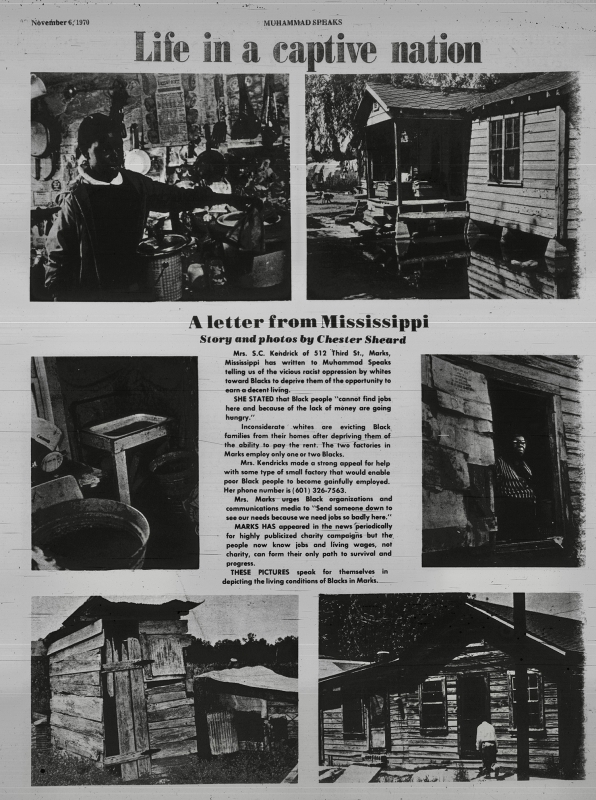

Focusing on the photographic credits suggests that housing is among the subjects that are routinely visually sourced by Muhammad Speaks. While most published photographs are uncredited, the cases where credits appear show that, quite logically, photographing houses is typically done by a reporter who provides his own images alongside his text. Among the credited photographs showing dwellings, except for a few images that are credited to external sources, the images for which an author is indicated span a wide range: the very simple image of “the house where I grew up” by a Black Muslim reflecting on his own trajectory (Minister Clyde Rahaman, “Minister Who Survived the Hell-Holes of Mississippi Thankful for Muhammad,” Muhammad Speaks, June 10, 1966, p. 25); simple outside views of dwellings to illustrate local articles, either to provide basic locational elements or to illustrate economic conditions, provided for example by a Muslim journalist called Nathaniel 10X, who regularly wrote and photographed for Muhammad Speaks from 1970 to 1975 (figure 1); but also richer documentary images, exemplified by Chester Sheard’s (figure 2). A regular contributor of texts and images, and sometimes photoessays heavy in housing photographs, for instance “Life in a Captive Nation” (figure 3), with pictures of interiors and exteriors of wooden houses in Mississippi, Sheard pursued a career as a photojournalist beyond his work for Muhammad Speaks, especially in jazz clubs (O’Donnell 2016). And while it remains difficult to assess exactly what was internally produced or sourced elsewhere, this duo of identified “housing photographers” indicates that the newspaper had its own regular and significant supply of housing pictures from the field.

Figure 1. Nathaniel 10X, “Mansions and Shacks Reveal Savage Rulers in Alabama,” Muhammad Speaks,August 25, 1972, p. 4.

Figure 2. Chester Sheard, “Surviving Politically in Mississippi,”Muhammad Speaks, February 5, 1971, p. 7.

Figure 3. Chester Sheard, “Life in a Captive Nation,” Muhammad Speaks, November 6, 1970, p. 7.

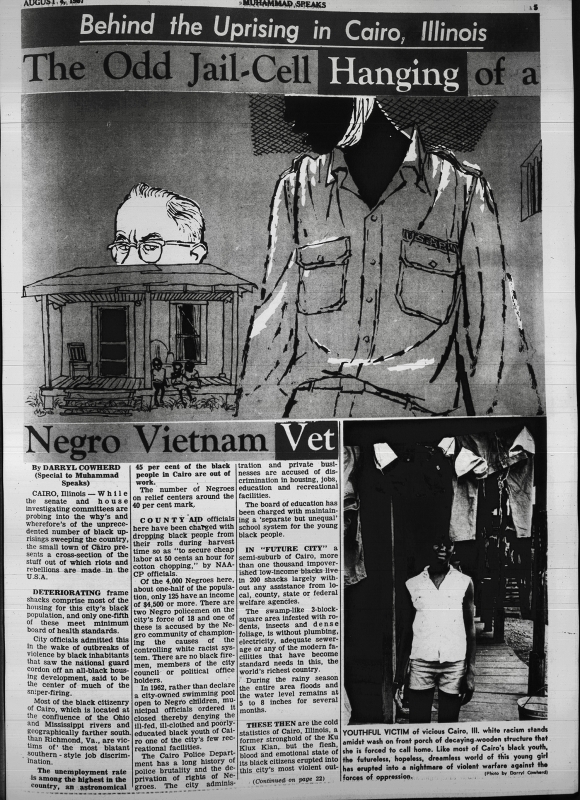

The editorial treatment of these images also shows various forms of capitalization on housing material: the basic ‘photo-essay’ formula mentioned above; the standalone feature with one or two images occupying some empty space in the layout with a more or less developed caption, standing in for a state of affairs and producing a focus on a sort of micro-landscape; full pages of visual reportage on Southern conditions. One page in a 1967 article about riots in the starkly segregated town of Cairo, Illinois provides several examples of the editorial treatment of photographs of dwelling, on a visual or textual level (figure 4).

Figure 4. “Behind the Uprising in Cairo, Illinois: The Odd Jail-Cell of a Negro Vietnam Vet,” Muhammad Speaks,August 4, 1967, p.5.

Photograph by Darryl Cowherd.

These riots were triggered by a hanging in prison, and the cartoon at the top pairs this scene (with window bars on the right that evoke a cell) with a front view of a wooden house, which is in fact exactly copied from a photograph from the same story published in the following issue (“Story of White Savagery in South Illinios [sic] ‘Hell Hole,’” Muhammad Speaks, August 11, 1967, p. 25). This ‘documentary’ basis for cartoons seems to be specific to housing. The social, political and economic conditions in the town of Cairo are illustrated by a photograph of a young woman standing on a porch; the trousers hanging from a clothesline over her stress that this is a domestic space, but they are also reminiscent of the hanging body of the man in the drawing—in fact the trouser legs almost align with the off-frame legs of the hanging body. This disturbing echo is just one example of the powerful and often strange visual editing, almost reminiscent of photomontage, that can be observed in Muhammad Speaks. The caption also includes a typical element of the editorial handling of pictures of housing, in its first sentence: “YOUTHFUL VICTIM of vicious Cairo, Ill. white racism stands amidst wash on front porch of decaying wooden structure that she is forced to call home.” The final words reject the assimilation between photographed domestic scenes and words such as “‘home,’” “‘shelter’” or “‘living’” room, often used in captions with quotation marks that call out the inadequacy of the space of reference. It should also be noted that the article describes the local housing to which African Americans are confined as “shacks.” This is a keyword in Muhammad Speaks, used to refer to most dwellings in the rural South (and often used in captions to name the architectural element in photographs of dwellings in part or whole). The quasi systematic use of this derogatory one-syllable word instead of “house” is all the more striking as Muhammad Speaks, edited by radical but veteran journalists who had worked for other media (Helgeson 2011: 209-122; Carroll 2017: 161), uses significantly more neutral language in its articles than The Black Panther, a publication famous for speaking “the language of the people” in Bobby Seale’s terms (Streitmatter 2001: 225). The houses to which African Americans are restricted are clearly subject to a special negative treatment.

3. Architectural structures and structural violence

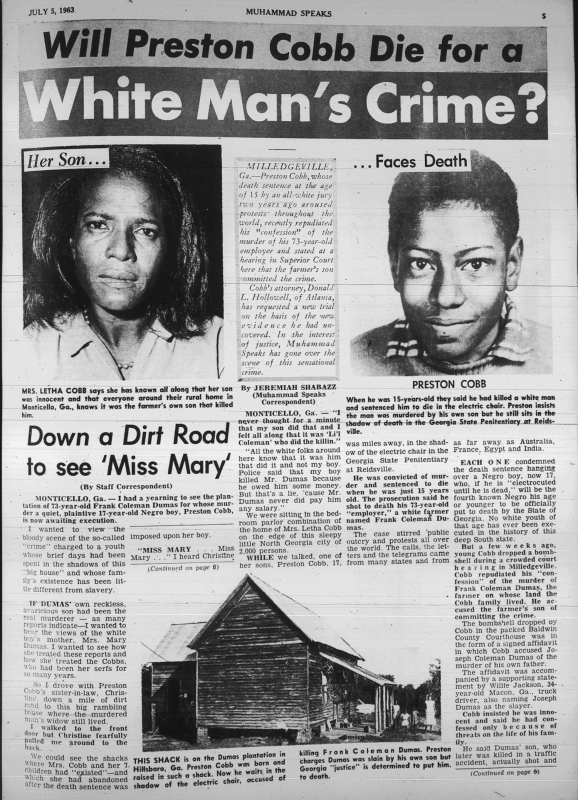

Figure 5. “Will Preston Cobb Die for a White Man’s Crime?” Muhammad Speaks, July 5, 1963, p. 5.

The newsworthiness of houses in Muhammad Speaks, and especially (but not exclusively) wooden Southern houses, corresponds to the capacity of this architectural artifact, closely cropped, perhaps accompanied by its dwellers posing in front of the house but exclusive of other contextual elements, to stand for a landscape of oppression. Take one set of photographs (figure 5), published twice in July 1963 and February 1965, at different stages of the judicial procedure that is reported on (“Will Preston Cobb Die for a White Man’s Crime?” Muhammad Speaks, July 5, 1963, p. 5; Jermiah, “World Protest Blasts Georgia’s Plan to Kill Preston Cobb,” Muhammad Speaks, February 12, 1965, p. 21). Headshots are combined with an external view of a wooden house said to be the home of a young Black man accused of a crime. If this allegedly simple visual material is published again after two years, it is also because the housing photograph offers a powerful entanglement on this page. The case involves gun violence, judicial oppression and economic exploitation: Preston Cobb has been wrongfully accused of murdering a man who is his landlord. The article stresses the racial power structure implied in the Southern agricultural system of land ownership; in the caption of the photograph showing a family lined up next to what is described as a “shack” on a “plantation,” the reference to the living conditions of the young man then leads to the mention that he is now “under the shadow of the electric chair”— a strange alignment, where the Jim Crow systems of sharecropping and criminal justice seem to collapse onto each other. The economic injustice of the post-plantation shack, rooted in the crime of slavery, compounds and foreshadows the more immediate injustice enacted on Cobb; it is both context and alternate materialization.

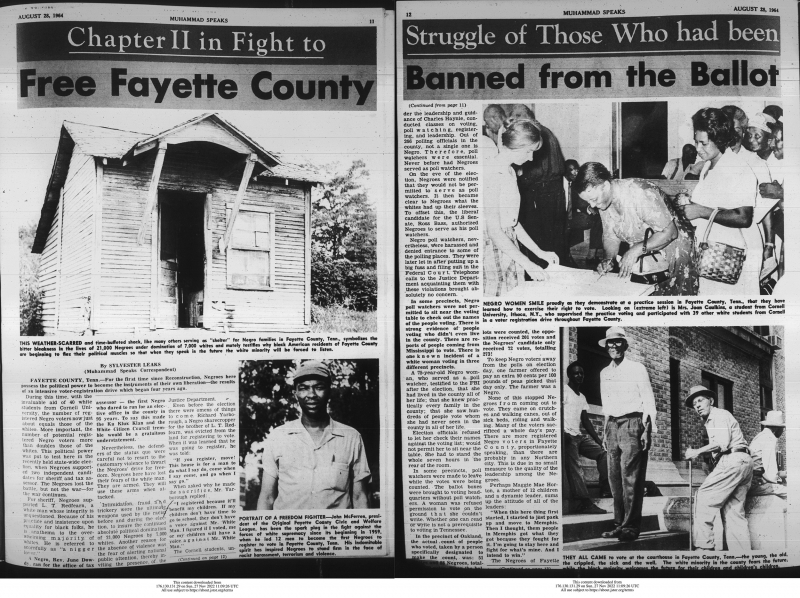

Still more striking, in the way it maximizes the house photograph on the page, is an August 1964 story on voter registration in Fayette County (Tennessee) (figure 6). It opens on a half-page photograph of one small wooden house, in a monumentalizing slightly low-angle shot. The ominous shadow created by a half open door and small porch adds a subtly haunted atmosphere. The caption is clear as to the rhetorical function of such an architectural artefact, described as symbol and mute testimony, which somehow gets the people in the next photographs moving:

This weather-scarred and time-buffeted shack, like many others serving as ‘shelter’ for Negro families in Fayette County, Tennessee, symbolizes the bitter bleakness in the lives of 21,000 Negroes under domination of 7,000 whites and mutely testifies why Black American residents of Fayette County are beginning to flex their political muscles so that when they speak in the future the white minority will be forced to listen [my emphasis].

Figure 6. Sylvester Leaks, “Chapter II in Fight to Free Fayette County,” Muhammad Speaks, August 28, 1964, p. 11 and 12.

The combination of the small house with its single window, and the groups of people registering and gathering in the next photographs, echoes the caption’s focus on the county’s 21,000 African Americans—each one of whom could somehow turn out through the open door. One could even say, after Ariella Aïsha Azoulay writing about Palestinian houses destroyed by the Israeli armed forces (2013), that such a house becomes a public square—a place where the disenfranchisement of a whole class of citizens becomes visible, can be discussed and denounced4.

Those are but two examples of numerous instances where inequality and exploitation, sometimes explicitly traced to slavery, are materialized by houses, their decayed porch, their run down and barren interior. The connections with violence are laid out by the accompanying text (as in the title of the Nathaniel 10X article in figure 2, “Mansions and Shacks Reveal Savage Rulers in Alabama”), or by the sheer fact of illustrating-through-architecture. Take the case of Nacogdoches, a Texas town whose ultra-violent policing and racist institutional treatment of African Americans was so shocking that it was covered both in Muhammad Speaks in 1971 (with images and texts by Chester Sheard) and in a series published by The Black Panther during the Summer of 1975 and April 1976. Sheard’s illustrations for Muhammad Speaks include three exterior and interior dwelling views, plus a photograph of a pair of hands. These views illustrate African Americans’ conditions in the town; they also stand in for photographs of violence that are not available to the journal. When The Black Panther covers the same policing practices several years later in its series “Nacogdoches, Texas: Racial Violence ‘A Relic of the Past,’” it relies on another type of alternate illustration, thematically closer but factually more remote, with old photographs of lynchings in Mississippi, Minnesota and Indiana in the 1920s and 1930s5. Lynching photographs are arguably the maximum intensity images that the radical press reproduces (Muhammad Speaks also published several of them in its early years)6. It is therefore all the more striking that in the fourth installment of the series, instead of a lynching picture, the article on Nacogdoches is illustrated by the photograph of two persons standing next to a wooden house, presented as “an example of the dilapidated housing which is prevalent in the rural South” (The Black Panther, September 1, 1975, p. 8). It is both another relic of the past and the materialization of a more chronic form of violence, effected through relegation and poverty.

The reading of substandard housing suggested here, as a visualization of structural forms of violence enacted on a whole racial and economic group, also rests on very explicit discourse in both publications at the turn of the 1970s, connecting housing conditions and the notion of genocide against African Americans. This idea had been conceptualized in the early postwar years with the petition “We Charge Genocide” submitted to the United Nations in 1951 by William Patterson and Paul Robeson. It was taken up again by Malcolm X before his death, as part of a turn towards the notion of human (rather than civil) rights (Nier III 1991). The BPP used the concept from the beginning of the movement, first to describe the way it was targeted by the US government, but also to denounce specific policies such as African American women’s disproportionate sterilization or undermaintained and segregated public housing (Roman 2016: 19-20). Articles stated that housing was involved in a genocidal plan in “the form of failure or deliberate refusal to provide shelter that’s fit for the housing of human beings” (Ronald Tyson, “When one walks through Boston’s South End, he is confronted by a scene that quickly reminds him of genocide,” The Black Panther, August 8, 1970, p. 3), be it in public housing or slum housing (“We Find the Slumlords Guilty of Genocide,” The Black Panther, November 21, 1970, p. 6). In fact, until 1971, genocide was linked mostly with housing and policing (Roman 2016: 20)—two salient aspects of neighborhood conditions.

Both the NOI and BPP saw genocide in sterilization and birth control programs targeting specifically African American women (Caron 1998). Interestingly, in both Muhammad Speaks and The Black Panther, articles on the subject tended to be illustrated by photographs showing women and children in their homes or on porches (“Can’t Be Mothers Again,” Muhammad Speaks, December 15, 1962, p. 4; Muhammad Speaks, May 1970, p. 19; “Sterilization–Another Part of the Plan of Black Genocide,” The Black Panther, May 8, 1971, p. 2). Muhammad Speaks was most steadfast in associating the notion of genocide with images of housing, an early case being a page of photographs by Chester Sheard, with a heavy focus in the captions on the materiality of housing detailed in the photographs, entitled “Silent Genocide: Mississippi” (Muhammad Speaks, November 29, 1968, p. 15); and the first really explicit instance being the publication, in December 1969, of a photograph by Bruce Davidson portraying a child in an alley, flanked with the U.N. definition of genocide in the caption, to illustrate an article about slums (“Government Agencies Say, ‘We Know How Bad Slums Are,’ But Slums Grow Worse,” Muhammad Speaks, December 1969, p. 5)7. The newspaper later introduced the phrases “genocidal conditions,” “genocidal living conditions” and “genocidal housing.” This conflation of genocide and housing is of course evocative of the terms “domicide” or “urbicide.” Here I however prefer to keep the formulas used by the newspaper itself, as they bear witness to a specific grafting of the concept of genocide onto an ongoing motif of concern and alarm, and also illustrate in their adjectival structure the practice of montage (visual and textual) in the newspaper.

In January 1970, the caption for a standalone photograph of a courtyard with wooden stairs and a family in the background started with “Genocidal living conditions have been calculatedly inflicted upon the Black people of the U.S. for four centuries” (Muhammad Speaks, January 16, 1970, p. 7). A few weeks later, an article about U.N. related news (an important focus in Muhammad Speaks through the decade), entitled “U.S. Fears to Sign U.N. Treaty against Genocide,” was illustrated by three photographs, including the view of a woman standing in a room strewn with papers, captioned “Mid-winter eviction” (February 27, 1970, p. 3). The caption reads the image in terms of government-guaranteed rights to work, housing, healthy food and medical treatment—and concludes that “the denial of these things to any people, nation or minority nationality is legally termed genocide.” While this is a scripting of a photograph in terms of human rights law, the facing photograph, which pictures a young girl in front of a house missing part of its sideboards, relies on a more sensorial texture: the girl “walks past the visible evidence of genocide,” thus supposedly made more tangible (in keeping with the many images of substandard housing in the journal). The caption repeats how economic and educational discrimination are part of the definition of genocide, albeit here “more subtle than Nazi Germany’s.” The face of housing, between sensationalism and systematicity, connects the journalistic work of compiling facts and reporting on conditions with the rhetorical work of sounding alarm.

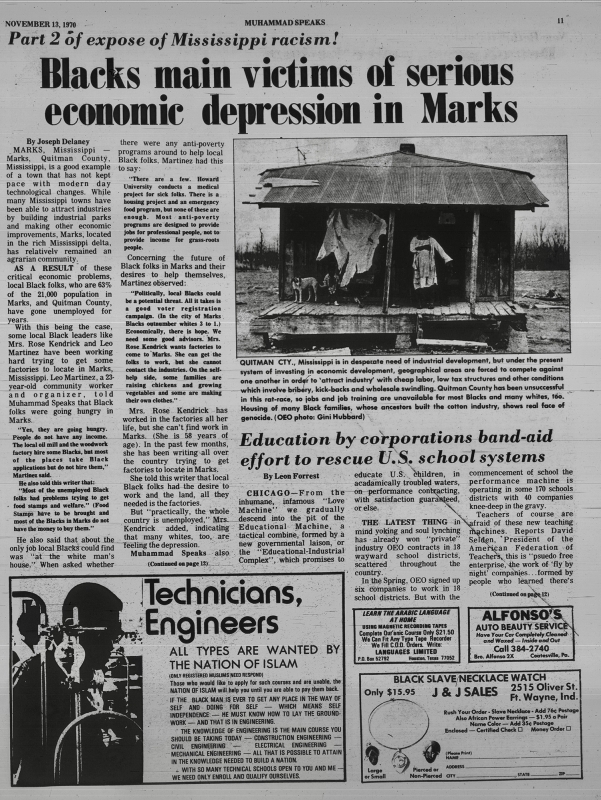

The mix of facts, concept, and texture, is illustrated in a particularly striking way in a later instance of a housing photograph portraying “genocidal conditions” (figure 7). In November 1970, an article focuses on economic conditions in Marks, Mississippi (“Blacks Main Victims of Serious Economic Depression in Marks,” Muhammad Speaks, November 13, 1970, p. 11). The article is illustrated by a frontal view of a wooden house, with a couple of inhabitants on the porch, taken by Gini Hubbard for the Office of Economic Opportunity. The caption is particularly precise, providing socio-economic reporting characteristic of the leftist editorial staff at the newspaper:

Quitman Cty., Mississippi is in desperate need of industrial development, but under the present system of investing in economic development, geographical areas are forced to compete against one another in order to ‘attract industry’ with cheap labor, low tax structures and other conditions which involve bribery, kick-backs and wholesale swindling. Quitman County has been unsuccessful in this rat-race, so jobs and job training are unavailable for most Blacks and many whites, too. Housing of many Black families, whose ancestors built the cotton industry, shows real face of genocide.

Figure 7. “Blacks Main Victims of Serious Economic Depression in Marks,” Muhammad Speaks, November 13, 1970, p.11.

Photograph by Gini Hubbard for the Office of Economic Opportunity.

The somewhat abruptly landing on the housing-as-genocide vignette shows that montage is at work at all scales of the iconotextual layout. Once again, antiquated and dilapidated housing conditions, here supplemented with the dirty and ragged clothes either worn or hung to dry, serve to bridge an individual situation (the photographed family) with a collective state of oppression. But precisely, the representativeness seems to preclude any other form of agency; the face of genocide may be visible, but that of the woman standing on her porch is missing, and there does not seem to have been any opportunity for “front performance” (Erving Goffman’s phrase) in an attempt to maintain composure or show a measure of agency (Aubert 2014: 13). The steadfast condemnation of the bad dwelling implies a relentless victimization of the dwellers.

4. Counter strategies, directed at or based in dwellings

12 Million Black Voices concluded with the evocation of a collective, interracial, Marxist vision of liberation:

The seasons of the plantation no longer dictate the lives of many of us; hundreds of thousands of us are moving into the sphere of conscious history.

We are with the new tide. We stand at the crossroads. We watch each new procession. The hot wires carry urgent appeals. Print compels us. Voices are speaking. Men are moving! And we shall be with them… (Wright and Rosskam 1941: 147)

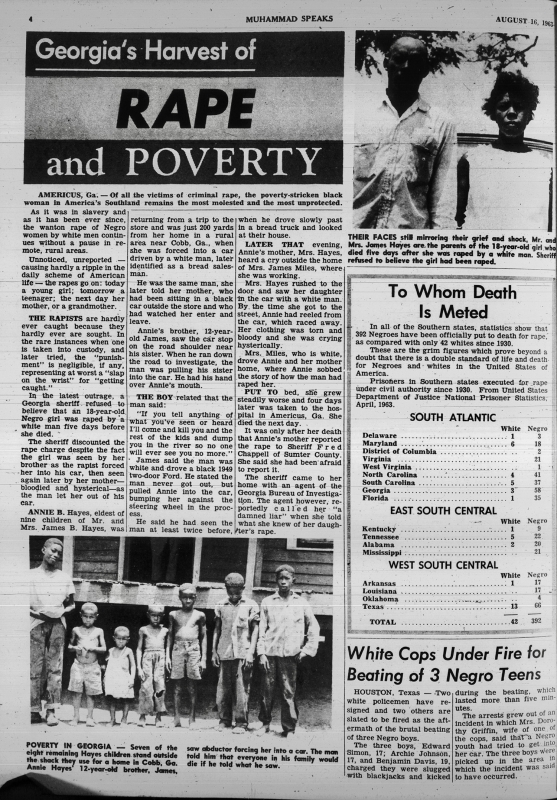

Those closing lines are followed by the photograph of a man looking up in the sun, on the doorstep of his wooden house. The shared future is here visible from the shack, even from inside the shack where the man must have been standing a moment before he was photographed; this is the opposite of the dark perspective in the gaze of the young woman of Cairo, Illinois (figure 4). The lyrical dimension of this photograph in 12 Million, its narrative opening, is different from the stark immobilization of the typical Muhammad Speaks version of the “doorstep portrait” (Aubert 2009). To take one more example of this formula: the children in figure 8, caught up by the lens, lined up dazed and unsmiling (but for one older child), cannot tell any other story than that of a harvest of poverty, as per the title of this article about a rape case (“Georgia’s Harvest of Rape and Poverty,” Muhammad Speaks, August 16, 1963, p. 3). And while any type of comparison between photography and rape should of course be treated with extreme caution, it remains tempting to read a faint echo of the subject of the article in the representational violence involved in such an exposure.

Figure 8. “Georgia’s Harvest of Rape and Poverty,” Muhammad Speaks, August 16, 1963, p. 3.

Quite typically, the caption refers to the architectural structure in the back as “the shack they use for a home.” The repeated treatment of the shack as a disaster, a site of horror, an anti-sanctuary, can in fact be contrasted with bell hooks’s reclaiming of the very word “shack” in an essay on domestic spaces, nurturance, and the beauty of Black lives: “Black Vernacular: Architecture as Cultural Practice.” The text is included in the collection Art on My Mind: Visual Politics (1995)—a book with an external view of a small wooden house reproduced on its cover. This essay traces the formation of a distinct, reassuring, empowering relationship to space that is grounded in the “lovely shack[s]” (149) of family and friends in the South during her childhood. “No matter how poor you were in the shack, no matter if you owned the shack or not, there you could allow your needs and desires to articulate interior design and exterior surroundings” (150). At stake is the reclaiming, for poor African Americans and especially for women, of taste, practice, and agency—all things that are negated, with no exception, in the visual treatment of poor dwellings in Muhammad Speaks.

Figure 9. Muhammad Speaks, November 14, 1969, p. S12.

The political project of the NOI was one of separation, and of building independent resources for African Americans. The newspaper’s end section, which at the turn of the 1970s deployed slogans and the program of the NOI, repeatedly included photographs of construction machinery, hospitals, factories, or new suburban tracts (figure 9) that should be “ours,” in the words of Elijah Muhammad; there was also regular inclusion of photographs and drawings of real or projected NOI real estate (especially in Chicago)8. The wholesale rejection of the shack must be read in relation with the NOI’s distinct project of uplift, also visible in the importance of uniforms. The distinct Marxist political orientation of the BPP is well rendered by the contrast in the housing horizons they offer: for the NOI, middle-class suburban housing; for the BPP, housing cooperatives. In the images published in its news organ, the neighborhood-based mobilizing strategy of the BPP is most visible in the presence of inhabitants, who are not presented simply as oppressed. With rare exceptions, adults and children are smiling; they point specific problems in their space; they raise their fists, carry signs. (In a 1969 photograph, a man seems to be raising his fist; he is in fact dangling a dead rat, while standing on a litter-strewn patch of grass across the street from a wooden house from which people are either moving out or being expelled: Bennie Harris, East Oakland Branch, “Denial of Decent Housing,” The Black Panther, March 31, 1969, p. 8. The dynamic, protesting figure directly echoes the tone of the article and the program point printed on top of the photograph: “We want decent housing fit for shelter of human beings.” The photographed man is clearly part of the “we” that is speaking and demanding.)

A final example, specific to The Black Panther, of how the dwelling can picture violence, is the drawings or serigraphs dramatizing self-defense from the heart of homes, in a more or less fantasized way, which is part of how Emory Douglas, the newspaper and more broadly the BPP leaders “visualized imagined agency” (Gaiter 2018: 300). While The Black Panther often included drawings of African Americans shooting pig-policemen, there are several instances of drawings that illustrate the slogan “shoot your landlord.” One example is a back cover by Douglas, with a woman sitting in her dilapidated interior, a rifle resting on her lap which is also for the moment directed at a rat hole (back cover of the September 12, 1970 edition)9. This is one striking visual instance of a woman (and an older woman) holding a rifle in The Black Panther. An earlier image by Douglas shows a woman standing on her kitchen table, fighting rats on the ground with broom and jug—in what is also a reversal of the stereotypical scene of a woman perched on a chair because a mouse is in the room (back cover of the July 25, 1970 issue). The text at the top asserts that this state of affairs gives her the right to kill “greedy slumlords.” An image that is reproduced on two back covers a few months apart shows a woman who has grabbed a big rat at the throat (back covers of the June 12, 1971 and January 22, 1972 editions). These non-photographic visualizations form a distinct subcategory of images, of literal fighting from everyday conditions. But the dilapidated interior is also the scene where after 1971 Douglas inserts small photographic fragments that appear as buttons on clothes or as frames on the wall, representing the party’s community programs and more specifically the breakfast program (which offers a collective service for a moment typically spent in the home) or advertising candidates in local or national elections (see for example the back covers of April 17, May 8 and May 15 editions). Instead of being projected as the architectural opposite of the dilapidated wooden dwelling, as in the real estate imagery of the NOI, the program is here “mounted” within the existing interior. The distressed dwelling is no longer photographed, but it is the richly textured location for the achievement, in the photographable present, of a communal organization; and in those back covers—a visual format often offering “empathic portraits” contrasting with the more disturbing cartoons inside the newspaper (Garter, 2012: 251)—the distinctly gendered space of the home, with its women and children, can be pictured as a place from where to practice both self-defense and nurturing, individually and collectively.

Conclusion

The stark differences in how both publications handle the distressed dwelling and its inhabitants under attack should by no means distract our attention from what these images represent in both cases: important space devoted to domestic sites along pages and issues, strong verbal and visual resonance for easily recognized architectural material, and a redefinition of built structures as tools of mass destruction. In years when urban riots could work towards deflecting any white guilt for living conditions in ghettos, through the motif of people perceived as being intent on destroying their own neighborhoods, this steadfast, creative coverage of oppressive housing units stressed that violence came from the outside, and was directed closest to bodies. With all these interior and exterior views of distinct dwellings and buildings, both destroyed and destructive, that are disseminated in both publications, it is as if the fait divers and the documentary had been merged, the most private space of the home transformed in an eminently public surface for measuring violence against a class and race-defined group.